As we head towards the end of summer, Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak are battling for the honour of being the fourth Conservative Prime Minister since 2016. The lines are seemingly drawn – Truss for tax-cutting, Sunak against, at least for now. Both, of course, claim to want to tackle the cost-of-living crisis.

Yet if there is a plan for affordable housing, it is hard to see what it is.

We certainly know the broad outlines. If nothing else, government policy will be big on the language of supply-side reform, with renewed calls to cut the red tape of planning regulation, unleashing a construction boom that will give us the homes we need, across all tenures. And if we worry about a shortage of social homes, it is the same planning reform that will answer our needs.

But it is, of course, the great promise of home ownership that will drive us all forward. This much is a given in Conservative policy. It is also the aspiration of over 80 per cent of the British population, and has been for decades. So an affordable and sustainable ownership policy is sorely needed, just as we need a bold and ambitious social housing plan.

Yet in the face of rising interest rates, too many owners will struggle to meet mortgage payments, and too many will lose their homes.

So perhaps it is time to rethink the balance of risk that owners must accept if they are to get on the housing ladder. Is the reward worth the risk?

For many owners, there are good reasons for doubt. I do not mean that the financial strain is too much for some budgets, and I am not simply asserting the need for a stronger safety net for owners. Nor should we doubt the need for a far stronger social housing sector, alongside a stable and functional private rental market. We certainly need all this.

But what about the good times? Is home ownership really the route to greater happiness and satisfaction? It is increasingly clear that it is not.

We can see this in the data I present in my recently published book, Social Housing, Wellbeing and Welfare. Using data from the British Household Panel Survey and Understanding Society, I set out to explore the relationship between housing tenure and wellbeing, measured by scaled questions that ask respondents how happy or satisfied with life they are. More specifically, I wanted to know the value of social housing for those who live in it. In the context of sustained media attacks on social housing tenants, I expected to find indications that this had a negative impact on personal wellbeing.

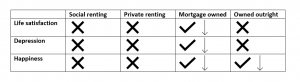

Yet the results surprised me. Even controlling for a wide range of socioeconomic variables, there was no discernable relationship between social housing and lower well-being. Not so for owners; or not, at least, for mortgaged owners. The table below summarises my findings. The ticked boxes indicate a statistically significant relationship between tenure type and my three well-being outcomes. They tell us that the relationship is either positive or negative, so the downwards arrows tell us that owing a mortgage is associated with lower wellbeing.

Summary of (compositional) tenure–well-being outcomes

In fact, the data shows that, compared to both social and private renters, mortgaged owners are more likely to report low levels of happiness and satisfaction with life, and are more likely to experience mental health problems. Much the same picture emerges when we compare mortgaged owners with outright owners. With the notable exception of happiness, outright owners fare better.

What is going on? One answer is clear. This is not simply due to the financial strain of paying off a mortgage. The model controls for income and, specifically, includes a variable on the extent to which people are struggling financially. Indeed, we see the same relationship all the way up the income scale, even among those who are not struggling financially. Nor can we attribute it to housing quality, or even satisfaction with the local neighbourhood. These are also accounted for.

Conversely, there is no relationship between social housing and any of the well-being measures I present. Perhaps this should be unsurprising. Most housing researchers know that social housing in Britain today has great social value, providing stable, high-quality homes for many people. Equally, however, housing researchers have also tended to hold the same assumption that I started with – that the constant media-trashing of social tenants must have some impact. It would be foolish to conclude from one set of data that it does not. But nor should we ignore the powerful, positive conclusion: social housing is good for personal wellbeing.

Where this leaves our miserable mortgagees is, of course, another matter. Perhaps their lower well-being comes from looking at the older generation of baby boomers, who so easily stepped onto the housing ladder. Right now we just don’t know. But if we want a sane housing system, we really should start looking.

James Gregory is a Senior Research Fellow at the Department of Social Policy, Sociology and Criminology, University of Birmingham.

Social Housing, Wellbeing and Welfare by James Gregory is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £24.95.

Social Housing, Wellbeing and Welfare by James Gregory is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £24.95.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Tom Rumble on Unsplash