The life of a diplomat may seem far flung and unrelatable but, beyond the cocktails and canapes, there are ideas that can help us understand and work on social issues, such as increasing polarisation, and lessons to help us support ourselves.

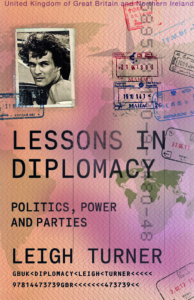

In this episode, Leigh Turner, author of ‘Lessons in Diplomacy’ and former British ambassador who led posts in Ukraine, Turkey and Austria, talks about the lessons we all can learn from diplomacy.

He divulges anecdotes from his career, looks at how diplomacy is changing and shares tips on how to overcome fear of the other and stay grounded in crisis situations.

Listen to the podcast here, or on your favourite podcast platform:

Scroll down for shownotes and transcript.

Leigh Turner is a former British ambassador who recently retired from the Foreign Office. Multilingual, he held diplomatic posts in Vienna, Moscow and Berlin, served as Ambassador to Ukraine, British Consul-General in Istanbul, Ambassador to Austria and UK Permanent Representative to the United Nations in Vienna, and Director of Overseas Territories in the FO. He has also written several political thrillers. Follow him on Twitter: @RLeighTurner

Lessons in Diplomacy is available on the Policy Press website. Order here for £19.99.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Leigh Turner © 2024

SHOWNOTES

Timestamps:

1:14 – How did you become a diplomat and why did you want to write the book?

3:42 – Can you tell us some stories from your career?

6:21 – What would happen if there wasn’t diplomatic immunity?

9:47 – Who did you write the book for?

13:17 – How does the book teach us about how the world works?

20:33 – Is the spreading out of power a good thing?

21:51 – What can diplomacy teach us about overcoming ‘fear of the other’?

27:36 – What is your advice for staying grounded and calm during a crisis?

32:46 – What does the future of diplomacy look like?

37:28 – What are your plans for the future?

Transcript:

(Please note this transcript is autogenerated and may have minor inaccuracies.)

Jess Miles: Welcome to the Transforming Society podcast. My name’s Jess Miles, and today I’m speaking to Leigh Turner. Leigh is a former British ambassador who led posts in Ukraine, Turkey and Austria. His new book, ‘Lessons in Diplomacy’, offers astute reflections on Brexit, Russia’s war with Ukraine and the chaos of modern politics. He sheds new light on the intricacies of modern statecraft, including what we can all learn from a good diplomat or ambassador.

Covering a variety of topics including dealing with crises, democracy, colonialism and getting to know the countries you’re working in. A life of a diplomat may seem far flung and unrelatable, but it’s not all cocktails and canapés. There are useful lessons in this book for social justice and social science, which we will talk more about here today. Welcome, Leigh.

Leigh Turner: Yeah. Hi, Jess. It’s great to be here with you.

JM: Thank you so much for giving us some time to record this with me today. The book’s fantastic. It’s really accessible. There’s lots and lots in it, and we won’t be able to cover everything today, but we will do our best. So let’s start. The book is you. You’re absolutely fascinating. So let’s start with you telling us a bit about yourself, how you became a diplomat and why you wanted to write the book.

LT: Great. Well, look. How did I become a diplomat? One of the key messages of the book is anybody can be a diplomat. You know, I’ve got pictures, in there. And which were in your photo gallery showing me as a teenager. And when I give talks I often say, if this guy can become a diplomat, anybody can become a diplomat.

JM: We’ll add a link to the photo gallery in the show notes of this.

LT: I mean, as a, as a as a child, as a young man, I was fascinated by the big wide world. And I thought becoming a diplomat would offer an unparalleled opportunity to get under the skin of different countries. So I applied, but I didn’t get in. I actually joined the departments of the Environment and Transport, which turned out, by the way, to be some of the most interesting jobs I ever did.

I talk about that in the book, but I was in their headquarters at number two, Marsham Street, a building which has since been demolished with three huge towers built in the 60s. Really ugly building. And I would sit in my office and look out of the window, and I would think if I have a really great career here in 40 years, I’ll be in a different window in the same building.

And I thought, there must be something more than that. And so I applied again to the Foreign Office, and this time I got in. And things, developed pretty well from there. I mean, as to how the book came about, my last job as a diplomat was as ambassador in Vienna, and it was a pretty tough time, to be honest.

We had, Brexit, Brexit was most of my job. And then we had Covid, I mean, two separate kind of plagues. But there were advantages, for example, because of Brexit every single person in Austria wanted to know why on earth the Brits were doing this from the president downwards, so that was good. And Covid turbocharged video conferencing, so I began mentoring other staff, mostly other heads of mission, other ambassadors around the world.

And this idea of giving something back at the end of my career took hold. So the result was I wrote 12 blogs, one for each of my jobs, with a lesson for each. These are kind of life lessons which are applicable not just for diplomacy, but for anyone, actually, I hope. for example, why you should take a proactive approach to your career and how to do that. And then a publisher saw the, blogs and asked me to write the book.

JM: Yeah. And there’s, chapter titles I think are really, they are interesting for everyone because it’s so varied, isn’t it? It’s like how to build your networks and communicate with people, how to…I can’t remember now off the top of my head how how to conduct yourself at parties, how to and then also the more serious like political bit as well.

It’s really it’s really well put together and it’s kind of like a collection of these fascinating anecdotes from your career. So I wondered if you could just tell us maybe a couple of stories now to give us a flavor of what the book’s about.

LT: Sure, sure. So some of the chapter titles, the first one actually is called How to Survive a Crisis and Number two is How to Tackle Terrorism. So those are big issue things. And then later on I’ve got one about how to know people, how to be interrogated, which is all about giving interviews and speeches, or how to craft a career so very general as well as very specific.

And, you know, the anecdotes, I include some very serious anecdotes. For example, I talk about diplomatic immunity, and I say how on the 17th of April, 1984, I was coming out of the office one day and I met a friend from the Foreign Office, and he said, “Something big’s happened at the Libyan embassy. It’s going to be on, on the news.”

And I thought, ‘well, what’s this?’ And it turned out that there had been a protest outside the Libyan People’s Bureau in London, which is the title that the Libyan embassy had at that time. And somebody one of the embassy staff had leaned out of the window with an automatic weapon and sprayed the crowd below with bullets. And this person had killed a police officer, Yvonne Fletcher, a British police officer, who was looking after the crowd.

So this led to a huge crisis. And the Libyans said, “Well, we have diplomatic immunity. You can’t investigate this crime. You can’t do anything. We demand to leave.” And the Brits said, “Well, no, we have to investigate this crime.” And the Brits and the Libyans said, “Well, okay, we’ve got a baying mob outside your embassy in Tripoli. I’m sure we can find plenty of crimes you’ve committed. and we’ll put all your people on trial, too.” And at the end of the day, what happened was that the Brits let the Libyans leave. All of them, even though we knew one of them was a murderer. And the British diplomats in Tripoli were able to leave, too.

So, as you can see, it’s something that remains. This diplomatic immunity idea remains very controversial, but it’s a kind of necessary evil. So that’s that’s one little anecdote. And then-

JM: Can I just a quick question about what would happen if there wasn’t diplomatic immunity, like, I suppose, what’s your thoughts on diplomatic immunity?

LT: That’s a very good question. So, so in countries where there is a rule of law where, the courts are independent and where the government can’t influence the courts, you don’t really need diplomatic immunity. For example, British diplomats are told you must always pay your parking fines. It sounds like a small thing, but it’s very important. Or if, you know, I was a diplomat and I did something against the terms of my, you know, I killed somebody, or I was stealing in, say, Germany or France.

I would go on trial, you know, I would not, the British government would waive my diplomatic immunity. But in countries where the courts are under complete control of the governments, for example, in Russia, it would just be too dangerous for diplomats to be in those countries without having diplomatic immunity, because the government could always trump up some kind of charge, as we’ve seen repeatedly recently in Russia.

Unfortunately. Journalists and basketball players, all sorts of people have been locked up and given long sentences, and then swapped for Russians who have actually been found guilty in the trial of killing, murdering people. So you unfortunately, you do need diplomatic immunity in some countries.

JM: That’s fascinating. Thank you. And I interrupted you. So it would be great if you could tell us the other story you were about to.

LT: Yeah. No I was just going to mention a less, a less serious anecdote but perhaps of great interest, which is how on earth do you get invited to a diplomatic cocktail party?

JM: How on earth? Tell me.

LT: You know, people long to get invited to these events. And if you’re a diplomat and go to them all the time, you think, why on earth would anybody want to go? You know, these boring speeches, long greeting lines, have to watch awful displays of folkloric dancing and singing and heavens knows what. But people do want to come.

And I think there’s three reasons. One is a sense of belonging. You know, people longed to belong to such an event as that. You know, maybe if you’re British, you’d love to go to the British Queen’s Birthday party or the King’s birthday party. The second reason is the reputation of embassies for skullduggery. You know, something weird is going on behind those high walls.

You know, wouldn’t it be interesting to get in and have a look and see what’s going on there? And then there’s status. People think, you know, high status people get invited to these things. I should be high status. I’d love to get invited. So as ambassador, I would often be faced with people who were literally in tears because they hadn’t been invited.

They wanted to be invited. you know, they begged to be invited. And it’s quite difficult. But there are ways that you can get invited. And and to find that out, you’ll have to read the book.

JM: Oh, actually, I’ve read the book, so see you at a party soon Leigh! Is there skullduggery in the background?

LT: Well, I’ve actually got a little section about espionage, and obviously there’s a limited amount I can say about it because of the Official Secrets Act. But, you know, there are many different ways that, people gather information about other countries. Most of them are legal, decent, honest and truthful. And sometimes we try very hard to find out information that other countries don’t want us to find out. So it’s a mixture of things going on, isn’t it?

JM: So as well as aspiring ambassadors, who did you write the book for? What do you want the readers to take from it? And maybe thinking of that skullduggery thing, does it challenge, preconceptions we might have about diplomacy?

LT: I hope it challenges preconceptions. It’s it’s designed to be a fun read. As I say, it’s designed to show that diplomats are just people like anybody else. But at the same time that it’s a really interesting career. And I think it’s aimed at two distinct groups. The first group is anyone who’s interested in foreign policy and how the world works.

I have, for example, a section on why on Earth do countries intervene in some conflicts. Let’s say in Somalia or in Iraq, but not in other conflicts like, say, Rwanda, or, Myanmar and the Rohingya. And these are really interesting questions. And so it’s a frank, often I hope, funny account of how diplomacy really is and how it works.

So I hope it will be very interesting to diplomats or wannabe diplomats, to reporters, to academics, to students, anybody who’s interested in international affairs. So that’s one group. And then the other group, really, I think that the lessons of diplomacy do apply to much of life more generally. For example, I have three top tips for diplomats. You know, one of them is be expert in whatever you do, really get into that subject and make sure you are the top expert on that subject.

A second one is take an interest in people. People really are the key to getting anything done in diplomacy and indeed in any other job. And then the third top tip for diplomats is be long term, you know, don’t decide everything instantly, no matter how tempting that is. Try and take a breath, pause, think about things before you make a decision.

So many of these top tips or these lessons apply to a lot of careers. Similarly, my top tips for ambassadors, I won’t go through them here, but they’re in the book. You know, they are true of many leadership positions. And I think and I hope that people will find a lot of the advice I give about diplomacy is actually true in many walks of life, from how to write a newspaper article through how to blog, through how to do social media, through how to craft a successful career.

JM: It is really true. When I was reading the book, obviously you go into it thinking, ‘Oh, my job is so far from being a diplomat or an ambassador, how is this possibly going to apply?’ But the way you’ve written it is really relatable. And even in my job you’re thinking because of that people bit and the leadership. But it’s how is how to relate to people in a kind and productive way, isn’t it? I think there’s a lot of that.

LT: People are the absolute heart of any job. It’s not just the job of HR, you know, it’s the job of if you’re at the bottom of the organization, you really want to know your colleagues, you really want to know your bosses. You want to know your boss’s bosses. If you’re at the top of the organization, it’s absolutely essential that you know everybody that’s working with you and that you understand them, so that you can motivate them so that you can find out what they want from the job and encourage them to do their best.

JM: Yeah. Then you get the best out of people and the best out of the situation, don’t you? This being Transforming Society podcast, I’m interested to go back to your point about how the book teaches us a lot about how the world works. So this podcast, we do tend to focus on social issues and social justice and it would be really interesting to talk to you about how that can be applied here. Could you speak to that a little bit?

LT: Sure. I, I do have a chapter, chapter 15 actually, which is how to make diplomacy reflect our changing world. And in during my career, which lasted all together 42 years, I saw many big changes in comms, in how we do diplomacy in all kinds of things. And just to highlight a couple, I talk a lot about women and diplomacy.

And one of the examples I give is, Margaret Thatcher. Of course, probably many listeners will think, well, Margaret Thatcher, not my favorite politician, but I saw quite a bit of her in my career, both, when she was prime minister and later, and her role as Britain’s first woman prime minister in a way reflects changes in society.

And I remember generally not being a big fan of Margaret Thatcher myself when I was working as a diplomat. But when I was writing the book, I researched the European Council of December 1987. So that was a meeting of all the heads of state and government of the then members of the European Community, and there was a picture of of all of them, it was 12 heads of state and government, 12 foreign ministers, and then a load of other people who were from the commission and so on at the summit in Brussels and out of all the 35 odd people in the picture, there is only one woman. And that is Margaret Thatcher. So, you know, whether you like her or not, she really had to put up with a lot of men in suits.

JM: Yeah.

LT: And then I look at how that has affected the foreign Office. And back in the day, back in 90 until 1972, any woman in the Foreign Office who was a diplomat or just working in the Foreign Office who got married, had to resign. Imagine that, 1972.

JM: It’s not even that long ago, is it?

LT: Really isn’t.

JM: Yeah. I was born in 1977…

LT: Absolutely. And then it took a couple of years after that. We had the first, ambassador who was a woman, and then numbers climbed very slowly by by 2012, there were 38 out of something like 160, female heads of mission. But it was argued that they were often very junior. So in 2018, taking an idea from Mary Beard, the professor of classics at Oxford, they instituted something called the Mirror Challenge inside the Foreign Office.

JM: This is brilliant. I remember this one.

LT: What it was was they took it, they took the 26 top jobs in the Foreign Office. And they said, has a woman done any of these jobs yet? And there were 13 out of 26 a woman had done so for those 13 positions in the Foreign Office they put in a picture of that woman, the first woman who’d done the job.

And then for the other 13, they put in a mirror. And the idea was that women or anybody, maybe an ethnic minority, could look or somebody with different sexuality, whatever it was, somebody who was disabled could look in those mirrors and could say to themselves, maybe I could do that job one day. And by 2024. So six years after they’d done it, ten out of the 13 mirrors had changed to being pictures of women.

So, big posts like Abuja in Nigeria, Berlin, Paris, Tokyo, Washington, New Delhi, they all had female heads of mission. So a huge change. And the lesson there is that if you really want to, you can change things and initiatives like that mirror wall can make a difference just by slightly changing the rules.

JM: Yeah, that’s a really interesting way of doing it as well. I hadn’t really heard of anything like that before in terms of ways of making change.

LT: Yes. No, it’s very interesting. I mean, think the example I give is how the world is changing and that’s changing diplomacy. So if you look back to 1945 and the setting up of the United Nations, there were five permanent members of the Security Council. They were basically the countries that had or might soon acquire nuclear weapons. So it was the Soviet Union, the United States, China, the United Kingdom and France and back after the Second World War, those countries had outsize influence on the world.

There weren’t all that many countries that had big economies that could operate armed forces around the world and so on. Now, as time has gone on, economic wealth and prosperity and the ability to influence things around the world has spread enormously. There’s a great book, I recommend it in ‘Lessons in Diplomacy’, called ‘Factfulness’ by a Swedish statistician called Hans Rosling, who says in the 1960s it made sense to talk about the so-called developing world.

But now in the 2000’s, it doesn’t really, because nearly all of those countries, which were lower income countries, are now as rich as Western Europe was back in the 50s. He makes a comparison between Egypt now and Sweden in the 1950s and saying they roughly the same in real terms, the roughly the same GDP per capita. And what this means is, of course, you know, there are still many very poor countries and there’s still enormous inequality in the world.

But what it means is that there are literally dozens of countries which can run a very sophisticated foreign policy and which can influence things around the world. And the voice and the military might and the economic might of the biggest and richest countries has got relatively much less. And what that means is that in order to get things done, for example, climate change negotiations, where it’s basically one country, one vote, you have to have much better, much more sophisticated diplomacy, and you have to be much more persuasive without being able to shake a big stick at people.

So although you might think that the world is still dominated by a few countries, actually it’s much less dominated than it used to be. And that poses both challenges and opportunities for diplomats.

JM: That’s fascinating. So power is a lot less concentrated, and there’s a lot more different countries to, with skin in the game. I suppose.

LT: Yeah. Yeah, yeah. So, well, I think the country has always had skin in the game, but they have more ability really to influence what’s going on.

See it in some very unwelcome areas as well, of course. But, more and more countries want to have nuclear weapons. They say, “Why should we obey the Nonproliferation Treaty, which says that only those five countries can have nuclear weapons? We want them too. It’s not fair. You know, they’re not getting rid of their nuclear weapons”, which is actually a pretty fair point.

And, you know, so we should have them, too. But no rational observer would want more and more countries to have nuclear weapons. So it does pose challenges as well as opportunities.

JM: What’s your overall view of that change? Do you think it’s, that kind of spreading out a little bit of power, is that a good thing generally? Does it lead to more balance and more kind of mutual decision making?

LT: I think generally it’s an excellent thing because it reflects hundreds of millions of people being lifted out of severe poverty. If you look at the statistics for China, for example, you know, a few decades ago, they had a big majority of its people were living on less than a dollar a day. They were they had extreme poverty, or in India or in much of Africa a few decades ago.

And now hundreds of millions of those people have been lifted into relatively good standards of living. Of course, there are still plenty living in absolute poverty, but far, far fewer than it was. So that’s a good thing. But it does mean, and one can argue it’s almost a political point, whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing, that it makes the world much more complicated to run. And no one little group of countries can really determine things in the way that was possible 40 or 50 or 60 years ago.

JM: Yeah. Which again, then changes the role of the diplomat I suppose too, I have a question about that later, actually. But first, we’re speaking now, it’s just a week after there were these awful, riots and far right attacks on immigrants in the UK. So I wanted to ask you about being such a polarized society. What can diplomacy teach us about overcoming this fear of the other, which I think underpins a lot of this stuff? And like, what can it teach us about ways of understanding people better in light of things like the riots in the UK last week?

LT: Diplomacy certainly can can help us understand and tackle some of these issues. I think. I mean, these really shocking disturbances that we’ve all seen, awful videos of confrontations on the streets of British cities, and they do reflect quite a few global changes. For example, technology that allows ideas to spread very quickly, unchecked in many ways through to a sense of disempowerment as the world grows more interconnected and people from many different communities, find it more challenging to integrate, or they find other communities more threatening to them because they pick up maybe completely wrong information.

Or maybe there are in some cases, there may be justifications for being worried about other communities. And so on. So what can diplomacy tell us about this? And as an example of the relevancy, I’ve talked about the United Nations, where there’s 193 member states in the United Nations. So to agree anything, you have to have a thorough understanding of the point of view of the other side of dozens or sometimes even hundreds of countries, many of those countries may have fundamentally different opinions from you and the diplomats you’re dealing with may be, you know, they may hate you, or they may just disapprove of you or disagree with you.

But the best diplomats in multilateral work, which means diplomacy dealing with more than one other country, like the European Union or the United Nations or whatever organization, the best diplomats build load bearing relationships through personal contacts, building up common ground and understanding on the toughest issues. You know, if I was in Vienna, I had to be in touch with the Russians and the Chinese, the Iranians, the Israelis, the Americans, everybody, no matter what their opinions on the issues we were dealing with might be.

And I had to know those people. And they in turn, with a few unfortunate exceptions, were mostly very professional. They knew that they needed to build up a relationship with me, too. And, you know, so a lot of contact building work went on to try and understand the other side. And this doesn’t just happen. You have to work at it.

And I think one can argue the same is true for societies as a whole. It’s isolation that breeds prejudice and stereotypes. I was very struck watching some of the rioters being interviewed later about their hatred of minority groups and there was an interview with one of them, who was asked, “Well, look, you’ve traveled from your town somewhere in the south of England all the way to Liverpool to protest against minorities there. But don’t you have those minorities in your town?” And the guy said, “Yeah, well, sure, sure. We do.” And, the interviewer said, “Well, do you not find them a problem in your town?” And the guy said, “Well, no, they’re fine in my town.”

JM: Wow.

LT: And the point was that when you’ve got contact with people, you you understand them much better. It’s as you say that other the people that you haven’t met, you can apply it to debates on almost any issue. You know, if you’ve never met a person of a different ethnicity or a different sexuality or whatever it is, you tend to think, you know, what are they like?

You know, would I get on with them? Whereas as soon as you’ve met them, in many, many cases, not every case, obviously, but usually you’ll find actually they’re fine. You know, they’re not so different from me after all.

JM: So the work of diplomacy is it sounds like it is then building those small individual personal relationships as a starting point. And then kind of the understanding spreads out from there.

LT: Sure. I mean, it’s partly, as I was saying, being being expert and really going into what the concerns of those particular communities or those particular countries might be and it is a lot of individual contacts. I remember, when I was in Vienna working on the United Nations, sometimes we would have a crisis on some new initiative that was coming.

And I had a number of people in my team. I remember one one woman member of my team, we had this crisis, and she said, okay, I’ll look into this. And in the next 4 or 5 hours, she phoned 30 or 40 different diplomats from different countries and tried to get their support for the UK position, try to understand what was motivating them.

And she wasn’t cold calling them. She knew them all already. Similarly, I remember I once had a point I had to get across to my Indian colleague in Vienna, and I went to call on him. I went to the Indian permanent representative for their United Nations office, and I met the ambassador there. And, and we talked about the issue as it was as it happened, I couldn’t win him over.

I can’t remember what the issue was, but I already knew him, you know. Yeah, I had met him many times. We’d been out for a meal together. I’d chatted to him on numerous occasions. There’s the famous cup of coffee at the UN canteen which people do all the time. And it’s about building relationships and understanding.

JM: One thing I think will really resonate with our listeners is your advice on staying grounded and calm when it feels like the world is going to hell in a handcart is the phrase you use in the book, could you talk us through this?

LT: Yeah, sure. Diplomacy does have a lot of crises. There’s always a risk of a bomb going off. Your own mission could come under attack, or you could have a big consular crisis where, a plane has crashed or a bus has crashed or during Covid, we had all sorts of problems with Brits who were stranded in Austria and couldn’t get home.

There are just constant crises and there’s a lot of practical advice in the book. As I mentioned earlier, one of the chapters is called How to Survive a Crisis, and I think there’s three key points about this that the first is that when you’re dealing with crises, training and muscle memory make a huge difference. If you’ve practiced and trained for what to do when X or Y happens.

For example, we did training on what to do if a lone shooter gets inside the embassy. What are you going to do to try and reduce the harm? Or what are you going to do if, as I said, if a bomb goes off, if you’ve done that training and you know, your role in a crisis, for example, in an embassy, you often have a crisis team that everybody has a different role.

They know what they’re going to do. They’ve practiced it. So, for example, when I was, I say in the book, when I was coming back from a weekend away, and my colleague phoned me from Ankara to tell me a big bomb had gone off in the center of Ankara. He was obviously very shaken by the experience. What should they do?

And I knew what we had to do. I was chargé d’affaires, so I was acting ambassador at the time. I knew what we had to do. I said, call together these people, we’ll have a meeting in an hour from now to discuss what to do. And we were all ready for it. So that’s one thing. Training.

JM: Yeah.

LT: And another thing I’ve mentioned already is summed up by a quote from a master French diplomat called Talleyrand, who addressed young French diplomats. And he said, pas trop de zèle. So not too much zeal or not too much enthusiasm. And the point he was making was you’re all full of the urge to do stuff, but sometimes you’ve got to take your time and do nothing.

This is really a difficult lesson in this time we’re in now with social media, and everything demands an instant response, and sometimes that means you don’t get the best response. You know, you you go off half cocked or as the Germans say, you go off in your trousers, you know, it’s it’s if you’re going to take an important decision, try, if possible to take your time and try to come to the best decision, not the quickest.

And this really comes to the third point, which is when you’re in a crisis to remember what’s important and what’s not important. I illustrate this in the book with the example of Robin Cook, who was Foreign secretary under the labor government that came in in 1997. And in August 1997, Robin Cook was on his way in a car with his wife, Margaret, sitting next to him when Alastair Campbell phoned him up, the press secretary from number ten Downing Street and said “Disaster, the news of the world has found out that you’re having a, an affair with your secretary or somebody in your office called Gaynor.

This is, a disaster for the government because it’ll make us look like we don’t have any morals. Quickly, you’ve got to decide within an hour. Are you going to stay with Margaret, or are you going to divorce her and have a relationship with Gaynor” and Robin Cook was literally in the car with Margaret sitting next to him.

Both Alastair Campbell and Margaret Cook have written accounts of this in their respective memoirs. So it’s it’s not private in that sense, but you have to feel a bit sorry for Robin Cook. I mean, even though you may have a moral position that he shouldn’t have been having an affair, to have to make that decision, which was going to fundamentally affect his life, Margaret’s life and Gaynor’s life so quickly made no sense. Just just so as not to embarrass the government. And, you know, a wiser government might have said, well, actually, whether one of our members of our government is having an affair or not, it’s neither here nor there, you know, look at look at what they do in France, where heads of state have affairs and nobody bats an eyelid, or in Austria, where nobody’s really interested in the sexual orientation or the peccadilloes of ministers as long as they’re doing a good job.

So those would be my three things for dealing with the crisis. Number one, training. Number two, take your time if you can. And number three, focus on what’s important.

JM: Yeah, it does apply to everything doesn’t it? Even like the way we we personally react to things going wrong or people saying things that we’re not comfortable with? We’re all often a little bit too quick to come back or about taking a breath and seeing the big picture, isn’t it a lot of the time? You spoke a little bit earlier about, diplomacy in a changing world, which is one of the chapters of the book and some of the opportunities that that presented and how it’s changed the role of the diplomat.

So I wanted to ask you what you think the future of diplomacy looks like. Towards the end of the book you talk about the impact of technology, and you say better communications have robbed foreign services of their gatekeeper function. So I’m guessing you would disagree that we’re seeing the death of diplomacy or anything like that. But there is something here in how that role of the diplomat is changing I think.

LT: There’s a lot in it. When I first became a diplomat, back in the 1980s, if a government wanted to send a secret message to another government or wanted to send a secret message to its own embassy in another country, it relied on the Foreign Office, or on its foreign service to encrypt a message, send it, decrypt it.

It was very labor intensive. Then you got computers doing it, but it was still really complicated. And the rest of the world, none outside governments, couldn’t send classified information. And probably they couldn’t speak each other’s languages either. So there was a, as you say, a huge gatekeeper function for foreign services. Now every phone has on it encrypted communications that governments can’t crack.

And huge proportions of the world, particularly in the professional world, speak different languages. Many people speak English, often with a British or an American accent. So the gatekeeper function has gone. But at the same time, I believe that the book should make clear that the need to understand other peoples and other countries will never go out of fashion.

I, I quote in the book, the newspaper, the Times from the 1870s saying, why do we need diplomats now? When you have the telegraph and you can send instructions immediately that arrive in real time at the other end of a telephone line. So why do we need highly paid ambassadors and experts out there in wherever it is, Istanbul or Beijing or Tokyo?

Back in 1870, it was the British embassy in Istanbul that just burned down. And the times were saying, why do we need such a big embassy? You know, we don’t really need these diplomats. But if you look at the big crises of the world, Russia-Ukraine, the Middle East, China, I mean, even the UK’s relationship with Europe, they all need people who have a deep understanding of other people, other cultures and other countries.

You know, diplomacy is, as I say in the book, in constant flux and communications are a great example. But I do think that understanding people and places remains as important as it ever was. And I don’t think that’s going to change in a hurry.

JM: Perhaps it becomes more important as well when you’ve got this information flying all over the place. It’s a bit like we were talking about with the riots, isn’t it? There is an increasing lack of people speaking before they understand another country or people in another country. So maybe the role of the diplomat somehow becomes more important as a balance and a measure to that, and an example of the kind of communication that works well and is progressive.

LT: Yes. I think that’s very true. And we often see it in individuals or even countries making decisions too quickly, without thinking about the consequences. One example is which I talk about terrorism in the book, and I say I don’t think terrorism is ever going to be cured or defeated because it’s just an intrinsic expression of of, people wanting to change things and, not necessarily for the better.

But I say that when a terrorist attack happens, it’s often not the best idea to respond for governments to respond immediately. There’s a there’s a famous book called A Savage War of Peace about the Algerian Civil War in the 1950s, which goes into this in some detail. And very often what the terrorist is trying to do is to get a government to react so strongly that it oppresses people, and that in turn breeds more support for the terrorists.

Yeah. So, you know, the governments have to be very careful about this sort of thing. And I think it applies in a host of fields that sometimes it’s best to take your time a bit before you decide. And get the best possible information you can before you take action.

JM: Yeah. Which goes back to your three lessons, doesn’t it? I have one more question, which is what are your plans for the future now? Now this book is done, and I know you’ve got lots of speaking engagements and things to do with the book, but what would you like to do next?

LT: Well, I can’t wait for the launch of Lessons in Diplomacy. It’s very exciting. I have, as you say, got a number of events lined up. If anybody else would like me to come and, talk to them about the book, I’m, I’m open to open to offers. So I’m hoping people will love the book. And I’m bracing myself for the fact that some people will probably hate it and criticize it. That’s just inevitable, but…

JM: Hopefully not too much. But yeah.

LT: The great testimonials we’ve got from everybody from, Jane Goodall to, Roger Glover, from Deep Purple to, Matthew Paris to all kinds of diplomats and international experts. They’re very encouraging. So, so, so I hope it’ll go well. And then I do write other books. I’ve written a series of novels, including thrillers, and some comedies and, and so I’m hoping that, if people like Lessons in Diplomacy, they might like them, too.

JM: It’s crime, you write a lot of crime fiction?

LT: That’s right, I do. Yes, indeed. Well, mostly international, you know, international thrillers. And then, I’m currently working on a set of comedies set in the Foreign Office, which is yet unpublished. So I’ll be working, on those and hoping I can get those published. So, you know, I love writing, and I’m hoping that people will enjoy Lessons in Diplomacy.

JM: Well, I, I’ve read it, and I can say it’s beautifully written. It’s very, very engaging and very, very easy to read. And you are kind of swept along into this world. And it’s a real, it’s a real mixture of very, very funny stories and then going into some quite difficult places as well. But you have written it incredibly well.

I might read one of your crime novels now.

LT: You’re very welcome.

JM: Which one would you recommend?

LT: Well, Blood Summit, which is set in Berlin around a terrorist seizing, a summit of world leaders, that’s, that’s my bestseller. so, you could start with that one.

JM: I’ll check it out. Thank you so much, Leigh. It’s been a genuine pleasure. Leigh’s book, Lessons in Diplomacy is published by Policy Press. you can find out more on our website. policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk. And you can get 25% of all our books by signing up to our mailing list. But thank you for listening.

If you’ve enjoyed this episode, please follow us wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you again, Leigh. It’s been really, really lovely to talk to you.

LT: Thank you very much, Jess, for having me today.

JM: Thank you.