As the US election approaches, MSNBC notes that the question of “what it means to be a man” is now a defining theme. In this episode, Jess Miles and Karen Lee Ashcraft revisit Karen’s concept of ‘viral masculinity’ — a powerful current of aggrieved manhood fuelling far-right ideologies worldwide.

They explore the manosphere, the online ecosystem where this resentment takes root, analysing how figures like JD Vance and Andrew Tate tap into youthful discontent and guide it toward political extremism.

Ashcraft argues that, much like a public health crisis, the rapid spread of aggrieved masculinity affects society at every level, shaping policies, identities and even environmental stances.

Offering tools for positive change, Karen discusses her concepts of ‘lateral empathy’ and ‘critical feeling’ as an alternative approach to defusing the far-right’s emotional momentum.

Listen to the podcast here, or on your favourite podcast platform:

Scroll down for shownotes and transcript.

Karen Lee Ashcraft is Professor of Communication at the University of Colorado Boulder. She grew up in the lap of evangelical populism, and her research examines how gender interacts with race, class, sexuality, and more to shape organizational and cultural politics.

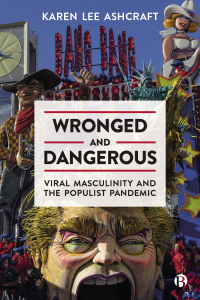

Wronged and Dangerous is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £19.99.

Wronged and Dangerous is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £19.99.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Gage Skidmore via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

SHOWNOTES

Timestamps:

01:19 – Why do we need to consider gender when talking about the rise of populism?

08:26 – How do you get from the manosphere to voting and politics?

15:23 – How do you explain female far right leaders like Giorgia Meloni and Marine Le Pen?

22:08 – Why is it important to envision the feeling of aggrieved manhood?

24:14 – Why do you see aggrieved manhood as a public health problem?

35:49 – What’s the problem with feeling and emotion being ignored in many contexts?

40:05 – How do individuals like JD Vance represent this viral masculinity?

48:25 – What is lateral empathy, and why is it an important tool?

56:11 – What are you working on now and what are your plans?

Transcript:

(Please note this transcript is autogenerated and may have minor inaccuracies.)

Jess Miles: Hello and welcome to the Transforming Society podcast. I’m Jess Miles, and today we’re doing something we don’t usually get a chance to do, which is a follow up episode. So almost exactly two years ago, I spoke to Karen Lee Ashcraft, who is professor of communication at the University of Colorado Boulder and author of ‘Wronged and Dangerous: Viral Masculinity and the Populist Pandemic’, which is published by Bristol University Press.

So with the US election just weeks away at the time we’re recording this, it would be remiss not to speak to Karen and revisit the book and especially Karen’s key idea of viral masculinity. The US network MSNBC have said that what it means to be a man has become one of the most dominant themes of the election. And as we know, it’s not just America.

Populism is on the rise across the world, and it’s usually explained by economic inequality, globalization and political polarization. But gender’s consistently absent from its analysis, even though this hyper masculinity is no longer on the fringe. So let’s find out more. Hello, Karen.

Karen Lee Ashcraft: Hello.

JM: Thank you for coming back and speaking to us again.

KLA: Thank you for having a rare follow up episode.

JM: I know it’s exciting.

KLA: Yes.

JM: So to kind of remind ourselves of the main ideas of the book, your main argument is that populism is driven by this aggressive masculinity. So can you start by reminding us why we need to consider gender, possibly even more so than class in an analysis of the rise of populism? And, could you please also explain what the manosphere is?

KLA: There is a lot in one question there, absolutely.

JM: Sorry, I do that.

KLA: No, it’s great!

JM: Let’s break it down.

KLA: Yeah. Maybe I would start with just a slight shift in terms since the book came out. I might use the term the far right and increasingly so as we discuss today instead of populism, and let me just briefly explain why. First, because in that two years, far right thinking is increasingly inhabiting the mainstream in many places around the world.

And so I think it’s important to acknowledge the extremism that has become mainstream, and also because it’s useful to create just a little bit of distance from that term populism to ask, and this is kind of what the book is trying to do, what is populism as a form? Do we here- is this really populist? What’s populist about the thing that we’re calling right wing populism around the world?

So I just wanted to start with that. That’s why I’m going to be kind of referring to the rise of the far right and kind of keeping populism as an open question.

JM: Yeah, that makes sense.

KLA: So if we could maybe, like you said, piece out that that opening fabulous question, the first thing you asked is why we need to be attending to gender, right? When we talk about the rise of the far right. And so, as you rightly point out, we rarely do so other than observing this kind of sideshow of hyper masculinity.

And instead we tend to focus on the common explanations, which are things like class and cultural marginalization. You mentioned political polarization, also immigration and demographic shifts, right, so racial and religious resentments. So I want to start not by refuting any of those usual explanations. Right. So it’s not that those are not key factors. Clearly they are involved.

What I am suggesting is that gender plays a particular role that we are ignoring, and that is the reason that gender needs to be called out. Right. So, I’ll say a little bit more about that, but I just I feel often that I need to say upfront in having conversations with people about this over the last couple of years, that I’m not making the argument that gender is somehow most or more important than those other factors, but rather that it’s doing something specific.

So here’s that something. What I am claiming is that gender is how the far right moves. Emphasis on the term moves. Gender is how the far right has been able to activate to recruit so many young folks around the world, for example. This kind of youthful injection of energy and gender is also how far right sort of notions and sentiments have been able to travel around the world.

Gender is what has made them so infectious, right?

JM: Yeah.

KLA: So I’m talking here about like you might say, gender is what has made the far right go viral, become communicable across very different cultural contexts. So, and languages as well. Right. So we can get more into the mechanics of that because there is actually something quite technical happening here. But what I am suggesting is if you put some of these usual explanations aside for a minute that we just talked about, and you ask a different question, which is, yeah, not just why is right wing populism, why is the far right cropping over a crop up all over the world?

But how is it happening? How is it traveling? Then you start to understand how gender is the mechanism of that travel. So if I were to be more specific, I would point out that it is no coincidence that in the last 15 years, the kind of online culture wars that exploded over gender, in particular, anti-feminism, as it is entangled with race, you know, sexuality, other things like that.

Those online culture wars have given rise to something that is now, I think, increasingly known as the manosphere. And what the manosphere has been able to do is galvanize this feeling of pissed off sort of manhood, like men have been wronged, men have been sidelined. It’s actually men who are the most oppressed straight white men. Western men have it the worst.

That feeling has been blown out across the world through the manosphere and is now sort of this renewable energy source for the far right. So that’s what I mean when I say gender is how it moves, that this feeling spread through the manosphere, intensified through the manosphere has become the emotional engine or the emotional, you know, power plant, you could say, of the far right providing a bottomless kind of recruitment pool.

Right. And fuel source. And maybe I’ll just say, for the sake of our conversation today, what I mean by like, I just kind of characterize the feeling of kind of angry manhood or manly rights wronged, but I’m going to use the term aggrieved manhood. In the book, I say aggrieved masculinity. I found people resonate with it more clearly when they get this idea that we’re talking about the feeling that real manhood has somehow, like, suffered injustice, right?

That we have- that feminism has unfairly unseated manly entitlements. And what we want to do is bring those back like real men are on a comeback, you know, so that’s that’s kind of the feeling we’re talking about it. It’s different than toxic masculinity, which I feel is where a lot of the conversations today are organized around toxic masculinity.

But aggrieved manhood is a response to all the conversation about toxic masculinity, right? It’s like, you know, feminists, by constantly calling masculinity toxic, you have hurt young men and boys. You have made it criminal to be a man. Aggrieved manhood is that kind of backlash to the toxic masculinity conversation. Okay, so I feel I’ve already only skimmed the surface of your question, and we still haven’t talked about the manosphere and what it is, but I want to turn it back to you to see how we’re doing so far.

JM: Yeah, we’re doing good. So just to I just wanted to look a little bit more of this, how it moves rather than why it moves, just so I can get it clear in my head really. So the only, the only person I can have, ever pops in my head with this is Andrew Tate. So you’ve got, so this how it moves.

It’s like, so you’ve got someone like Andrew Tate who comes through on YouTube or wherever he used to be, and he’s talking to men, lots of young men and boys, and he’s doing his thing, and he’s kind of stirring up this aggrieved manhood in them as well. Isn’t it? And does this affect populism because within that manhood comes all the other beliefs, like the aggrieved manhood leads to particular beliefs about women, leads to particular beliefs about immigration.

And then they kind of latch on to Trump or Bolsonaro or whoever. I just wanted to kind of unpack what is, what the process is there. Like, how do you get from within the manosphere, which I think we haven’t really talked about that yet, but I kind of see that almost as like the online. It’s almost an online world, isn’t it, where ideas and information are being exchanged.

How do you get from that to voting and politics?

KLA: Well, let me start with the short answer and then a longer one. So the short answer to your question, is it a gateway drug? Basically is aggrieved manhood a gateway to, to some of the other kind of hatreds. Yes. Is the short answer. And in fact the far right is quite clear about that. And in fact, there are all kinds of toolkits and, guidelines for how to recruit young men that specifically, say, begin with the anti-feminist issue, begin by just sort of softening.

They call it the slow red pill. Begin by sort of softening the feeling of like, don’t you feel kind of bad for being a young white man today? Doesn’t it kind of hurt to be the only one who’s always the bad guy, right? And I mean, there’s there’s so much explicit guidance on this in terms of the branding of the far right that you should begin with this issue.

So it’s that’s not actually a novel argument I’m making. I’m actually using their own kind of branding, and they truly are branders. We don’t often think of it as a marketing force, but they are monetizing this for a reason, and they’re aware that that is kind of the adhesive. That’s the sticky thing that will make all of these other things more palatable.

Later perhaps we’ll get into a conversation about how in much of the ideology of the far right gender, sexism, homophobia, anti-feminism, misogyny is deeply integrated with the white supremacies, with the white nationalisms, with the anti-Semitism, anti-Muslim sentiments. So it’s really important that we both see those all as one piece, the term people use these days is intersectionality, but at the same time, call out the role of gender, which is gender is how it becomes emotionally seductive.

JM: Right? And you can see it’s appealing, isn’t it. Right?

KLA: Yeah.

JM: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

KLA: It’s an identity politics, right? It’s an identity politics that basically everyone else has had at their expense. That is what aggrieved manhood is telling them, right?

JM: Yeah.

KLA: Now, the other answer to your question, I said there was a short and a long, is you know, when I talk about shifting the question from why to how, and we can use Andrew Tate as an example here. I think often when we’re trying to understand, like why something occurs, we ask, what reasons does it give?

What are they saying, what grievances are they putting forward? Are they class grievances? Are they race grievances? Okay, that must be that must be why it happens. And that operates around a kind of old model of communication which does not fit the communication landscape today. So what it presumes, that older model, is that information and ideas, ideologies are in the driver’s seat and feeling follows those.

JM: Right. Okay. Yeah.

KLA: So you know like it’s class, it’s socioeconomics. And that causes people to feel resentful. Right. Class marginalization, cultural marginalization. But in the world we live in where online culture wars, social media, participatory platforms have completely altered the relationship between our bodily feelings and the networks we’re engaged in, feeling is in the driver’s seat. Feeling is in the driver’s seat.

This is something that communication scholars who talk about what is termed communicative capitalism. There’s other terms for it, too. This is what they’re charting the ways in which our analysis need to be leading with feeling. Because feeling is in the driver’s seat and content is getting attached to it. Content is like a vent for it or an outlet, but we keep asking questions of cause that are focused on content, if that makes sense.

So this is what this is what I really mean.

JM: It’s a bit back to front or that all the steps aren’t in there somehow. Yeah.

KLA: So if I, if, if we were to just distill that, we would say instead of listening to what the far right says, follow how the far right spreads, instead of listening to what it says, follow how it spreads. So the question is not why, for what reasons, but rather how like on what energy? How is it able to spread around the world?

Why do these culture wars look so similar? Why is everyone doing the anti-trans thing? Why is everyone doing the anti-woke thing, albeit in local ways, right? Why is everybody upset about the gender binary? Like, these are the questions I want to ask. How is that repetition occurring? And to do that, you have to look at the traveling of the feeling that is binding those developments.

Does that make sense?

JM: It really does make sense. And it’s interesting, isn’t it, because this is happening in all these different places and like places that are potentially quite different culturally. And yet it’s such a strong theme. So that guy is it Kickl in Austria got elected last week. Yeah. It’s just kind of popping up. So aggrieved manhood is this emotion and this feeling that makes people perhaps more, well, does make people more likely to go towards the far right?

How do you explain female far right leaders like Giorgia Meloni and Marine Le Pen in the context of this?

KLA: This is such an important question because the number one, I would say resistance that people have to this idea that gender is how it moves, is it can’t be masculinity because women are doing it to. To which I emphatically say, never let the idea that women are participating in something throw you off the scent of gender. Never let it throw you off the scent that masculinity, a threat to manhood, is involved.

Rather, what you can do is use the kind of women involved and the way in which they’re involved to help you get specific about the form of masculinity we’re talking about. I mean, another way that I like to put this is have you met heterosexuality? There are so many reasons that women have to get invested in, you know, masculinity and its so-called oppression.

Right. As wives, as daughters, as, you know, sexual partners, economic partners, heterosexuality offers women all kinds of carrots to get invested in maintaining that system. And so you will regularly see not only women at the helm of right wing populist parties, but you will watch the particular role that they play to soften it, to give it some heart, to show that if women do it, it must not be just about men, right?

To play that sort of family card. The concern about our children and mothers, right. But all of their investments are through heterosexuality. So that tells you we’re not talking about all kinds of manhood. We’re talking about heterosexual manhood. Then you look at the overwhelming participation of white women in many different kinds of contexts. It’s not that only white women do, but overwhelmingly it is white woman.

Right. Okay. So that tells you there’s a racial element to this masculinity. So when aggrieved manhood claims to speak for all men, no it isn’t. It’s speaking for straight whites. You could continue to specify it by looking at the folks who may not seem to fit the category, but nonetheless find reasons to be invested.

JM: So what we’re saying is some women get enough out of heterosexuality to become part of it and become aggrieved on behalf of manhood?

KLA: They may also get I mean, heterosexuality is perhaps the clearest example of why women are not only emotionally but economically invested because of the way we make economic units through heterosexuality. But you can also look at in the US context, I’m not sure how familiar they would be to your listeners, but like Marjorie Taylor Greene, for example, and there’s several women who fit this profile in many different national contexts who, like, get props for embodying it, for actually inhabiting, like pissed off white manhood.

It separates them from other women, makes them seem cooler, better, smarter, edgier. Do you know what I mean?

JM: Yes, I can see. Yeah, I can see that.

KLA: So there’s that element too, right? I mean, as somebody who, grew up surrounded by aggrieved manhood, I not only have embodied it during my lifetime and been invested in it, I always, like I know what it’s like to get that sort of puff of like, yeah, but I’m not like those other, you know.

JM: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

KLA: So it’s that sort of investment too. This is why I continually emphasize that the kind of gender analysis we’re after here is not about men and women per se, or gender identity. It’s about gendered feeling and how we can all inhabit it. And when a feeling goes viral, what is the trajectory of that? What where is it going?

Right. It’s going to find many different mouthpieces. But the point is to really zoom in on the feeling, as if the feeling is an actor or a figure itself. Right? So we can think of, I think the tendency coming back around to your point about Andrew Tate, the tendency is to focus on a particular mouthpieces JD Vance, Elon Musk. Tucker Carlson, Andrew Tate, Russell Brand. Right. And we all have thoughts about these particular figures. But we miss the circuitry, the economy, that binds them all together. And in fact, it is that network we should be concerned about not any particular mouthpiece. And that is the network I’m referring to when I use the term manosphere, it is a massive economy and I mean that literally.

Big business and small, small time influencers and, you know, huge industries invested in this. And it is all about sharing and trading and growing the attention economy for this feeling of aggrieved manhood. So you have everything from individual trolls and cyber stalkers and, you know, online misogyny, hate campaigns to men’s wellness stuff around bodybuilding and enhancing semen counts too.

Right. So Andrew Tate is just one small node who gives us a window into the kind of thing that boys are encountering all the time. And it’s not just what they’re encountering. It’s not just toxic notions of manhood like, oh, Andrew Tate. They are encountering a viral environment where they are saturated with this feeling day in and day out.

This is why I say viral masculinity of this sort is more concerning than any toxic ideas that it is sending around, because it is basically creating like a sea of aggrieved manhood in which we all swim, but especially young boys and men.

JM: Yeah, I think maybe I when I read your book and I did read it again before this podcast, it’s almost doing the idea a disservice, I think, to impose the concept onto individuals like all these men we’ve just talked about. And it’s about getting your head to visualize this emotion and this feeling. You talk about a pufferfish don’t you in the book.

And I wonder if that’s the symbol I need to get in my head to visualize the feeling and go from there.

KLA: Thank you Jess, because that is precisely why I talk about that. And when I give talks about this, I have begun to introduce aggrieved manhood as a character. That’s how I, I start by embodying it because I have such experience. And then I ask audiences to, like, watch what my body is doing. The flares, the pulses, the puffs.

You can’t see Jess, but she’s doing it right now.

JM: I’m doing like the shoulders back, pump the chest.

KLA: Yeah, yeah. And the idea is like, I am a self-contained person, I am invincible, I am impermeable. Don’t tell me that real manhood isn’t strong. Real manhood doubles down on toxic masculinity. Picture everything from Donald Trump’s mouth to all of his spokespeople who the kind of bluster, bravado, even intellectual sort of innuendo. It’s all about this sort of puffer fish lashing out barbs style, right?

Which is proving the invincibility of a kind of self-contained man. And it is that repetitive feeling that I want people to notice, and not any particular spokesperson or any particular victim of this. Right. Any particular person who comes to feel it like.

JM: Yeah.

KLA: Many people can be vessels of this feeling, women included.

JM: Yeah, yeah. And it’s a really interesting exercise, I think, to imagine the feeling. And then that helps. Yeah. It helps me anyway, to understand the argument, I you said something just then that made me think about this idea in the book. That and it’s quite a controversial idea in the book. I think that this is actually a public health problem rather than a problem of democratic decay.

That’s a really interesting idea. Can you explain how you see this as a public health issue?

KLA: Yes. I’ll explain why I see it as a public issue, a health issue, and also why I think that is an important frame in relation to the kind of threat to democracy. So let me start with a public health issue. One of the things I’m at pains to document in the book is the way in which the feeling has gone viral that is circulated, intensified, occupying ever more contact points right with our bodies.

And as a result of that, we see a number of things that have basically elevated the health risk of the general population. And this is what I mean by a public health problem. Perhaps the most vivid example, and I realize this centers a US context but I think it makes the point, is mass shootings. Which we can agree have gone viral.

Right? I mean, I chart those statistics. I demonstrate the connections between shooters, how we should not see this as a lone wolf movement, but as an actual kind of digital organization where they are mimicking one another and see themselves as part of a social movement on behalf of aggrieved manhood.

JM: Do you think you can always, is it fair to always link mass shootings to aggrieved manhood?

KLA: So not always. There are certainly exceptions, but this is why I parse the data kind of carefully. Because you could say overwhelmingly, mass shooters are not only men, but white men. But it isn’t just about who does it. You have to come back to the feeling. So you look for evidence of kind of radicalization or, you know, coming to be inhabited by the feeling.

And there are cases even of women mass shooters where that is present. But people aren’t digging into the data that way, right? People aren’t digging into the data that way. So that’s what I’m careful to do, is say it’s not just because it’s associated with men. I’m trying to show you the ways in which aggrieved manhood has raised the risk of mass shootings in the US.

Yeah, it’s a it’s a complex argument, but it certainly has. And what that shows you is where aggrieved manhood is obviously associated with all kinds of supremacy crimes, increasingly, we have a situation where there’s collateral damage to intended supremacy crimes all the time. Right. So so that being in the public is basically putting you at risk of being somehow in the way of these supremacy crimes, right?

Mass shootings are an example, but they are not the only example. Right. Stabbings or other sort of public bombings, you know, whatever the case may be, using driving trucks through sidewalks, I mean, like the general public is increasingly at risk of these kinds of crimes stimulated by activated by aggrieved manhood. So that’s one. But another massive example, and perhaps the most troubling is the way in which aggrieved manhood puts the planet at risk.

JM: Oh I was gonna ask you about that. Yeah.

KLA: Yes. A huge part of aggrieved manhood is, remember that pufferfish, remember that like, I don’t need this mask. I don’t need to recycle. I eat meat times three. Oil and gas industry. Hell, yes. Like I’m rolling coal on my diesel engine. You know, it is increasingly the case. And there’s all kinds of researchers that have, documented this beautifully around the world.

That manly grievance is associated not just with climate denialism, but with social move- anti green social movements and what they call climate destructive lifestyles. And then scale that up to the places such as the U.S, where aggrieved manhood has occupied, high positions in the government and can kill climate legislation can pull out of the Paris accord, right?

So in essence, aggrieved manhood gone viral and it’s conviction that we can just ignore climate change is a death sentence for the planet, or at least for humans. But, you know, even so, here we have two examples. We have-

JM: So can I say about the climate change example. Sorry to interrupt you, it’s really interesting, I think because with the climate change thing, you often think, oh, it’s big business that’s preventing it and it’s economics, and it’s because people want to make money, and that’s why these policies aren’t coming through. That would probably do something to stop climate change killing us all.

But this aggrieved manhood is part of it as well. And it goes back to that populism argument of like we explain it through economics, and it’s a similar thing again, isn’t it?

KLA: I’m so glad you said that. One of the things that I have begun to try to talk with people about is the ways in which corporations want aggrieved manhood. And so because if you let’s let’s use to make this extremely tangible your example of Andrew Tate, who famously got-

JM: I hate always using him as an example.

KLA: But who famously got into that delicious squabble with Greta Thunberg, right, about his many cars and their respective huge emissions.

JM: Yeah.

KLA: By which he was embodying what I just said, the ways in which aggrieved manhood is about a climate damaging lifestyle. So he is taunting, you know, this sort of feminized image, which it often is in my, country, AOC is is often this character, women who are associated with green movements. So he’s targeting Greta and just doing this sort of puffery.

Okay. So so he embodies that. And, you might say, why is it that he’s able to find so many sponsors and that right? Why? Who are all the investors in the influencers, big and small, who are intensifying this feeling? If it appears to come from somewhere else, if it appears to be a sort of grassroots swelling of support for the killing industries, for oil and gas, then like the activities, the destructive activities, of all kinds of corporations are out of the limelight.

Right. so there’s actually an investment in stoking this feeling on the parts of business interests where they would seem not to be involved at all. It’s a huge distraction that draws everybody to the sort of legitimacy of this angry man movement. So that’s an extremely important point.

JM: I feel like it’s particularly terrifying because we’re talking about feelings and emotions here. I wonder if, like a lot of this is happening on a subconscious level as well. So you have, I don’t know, business leaders, people making decisions about sponsorship, and they look at the numbers on the paper and go, okay, if we do this deal with this person, then financially that’s a good thing.

Perhaps not really acknowledging that they’re being driven by some kind of aggrieved manhood into making that decision. And it’s all kind of happening. I can’t explain what I mean. It’s all happening kind of under the surface somehow and can be justified by financial decision. yeah. It’s scary because people might not even realize they’re doing it.

KLA: That is one of the central things to contend with. If we acknowledge that a feeling like this, which has gone viral, is in the driver’s seat then no one agent is exactly in charge anymore, right? And that is what I’m trying to contend with, is in the way is the ways that this operates under the radar and sort of off the edges of awareness, both for people, individuals, but also for people who think they are opposed to it.

JM: It’s yeah, yeah, yeah.

KLA: Corporations who may embrace a social justice agenda and nonetheless feed into this. And this is why I wanted to mention not just why viral masculinity is a public health concern, but why it is important to frame it this way, because I think there is a tendency when we start talking about it’s a threat to democracy. We are replaying an old script, which, you know, many historians have talked about Thomas Frank as an example, which is anti populism.

Yeah. Which is like, oh, these, these angry guys are just lowbrow and crass and regressive and backwards and they’re a threat to democracy right. Okay. So that is actually pouring fuel. That is its own kind of charging of this feeling.

JM: Yeah.

KLA: Contributing through it through this sort of like rejection of it like giving it all the reason it needs to get even angrier, raise its fists even stronger.

JM: It’s more of what aggravated it in the first place. Yes, yes. Yeah.

KLA: So I’m trying actually to not approach aggrieved manhood in an anti populist way, but to actually reclaim populism from aggrieved manhood, like to to basically say, you know what? We all have a vested interest. If there is one thing humans share, it is stopping the flow of this feeling. And that is true even for those who are feeling it, who are advocating it.

It is bad for them. And I have tried in the book to make that case as well. For example, focusing on how gun suicide is associated with aggrieved manhood. And now that, yeah, white men in certain parts in the US are at a statistical risk of gun suicide as a result. Right? So it’s like this doesn’t benefit anybody.

And it’s extremely populist to sort of take up this shared concern of the people. Right. And to say, aggrieved manhood. I’m I’m calling foul on that populist mask that is serving your selfish interests. And they are in no one’s interests. Right.

JM: I can see why you’ve moved from using the term populism towards using far right, because populism isn’t far right. Like, yeah, yeah, yeah.

KLA: And there’s I’m not I mean, you know, partly it’s a, it’s a matter of how I grew up, but also knowing the history of what populisms have and have not done, I’m not inherently anti populist.

JM: No, no.

KLA: And I actually think that by claiming populism, aggrieved manhood has created some interesting bifurcations that on the left we feed into just pouring that fuel on the fire. So I’m trying not to participate in that by turning towards something in which we all share an interest, which I think is public health. Well, the well-being of everyone. Right?

JM: Yeah. Speaking to you now also makes me realize the extent to which feeling and emotion gets ignored in discussion generally. So gender’s obviously been ignored in the context of far right populism. Far right. But generally like in academia, in like in all areas of our lives, we never we don’t often hold feeling and emotion as this systemic thing in the way that you do in the book.

And that’s really interesting, too. I think it’s more convenient is it is a bit is quite difficult, isn’t it, to engage. Yeah, yeah. To get our heads there somehow.

KLA: Yeah. We talk so much about misinformation and disinformation, tracking those flows, getting better ideas in front of people. And all of that seems to be focused on the notion that when people are radicalized toward the far right, it’s coming from the ideology, like, you could say, the cognition or the head is leading.

JM: Or the the beliefs.

KLA: The beliefs or the yeah, yeah, yeah, there’s a kind of idea based persuasion or maybe even value based persuasion that is occurring. But what I demonstrate in the book is how the manosphere operates by a different practice, which is physical radicalization first. Now, let me underscore that I am not trying to say it’s one or the other.

I’m not saying it’s all feeling and no ideology. They are in close relationship. I am asking people to shift the emphasis. We are we are fixated on the content and we need to pay attention to the feeling, right? So when I say yeah, when I say physical radicalization, what I mean is you can take, you know, any of the manosphere’s classic hate campaigns that listeners might be familiar with.

Like, you know, ten years ago it was Gamergate. And the idea was getting all these young boys basically playing politics like a game. Like clicking, shitposting, trolling, one upping one another like, yeah, like this anarchist. Do you see? I mean, I’m now embodying. That popping up again? Like, yeah, the rush and the thrill of gaming politics.

Watch JD Vance speak. This is what he was reared on. This is what he is embodying, right. And so it’s an almost like I don’t maybe mean the language of addiction literally. But it’s like the body gets addicted or habituated, conditioned to the pleasure of this lashing out, this backlash. Right. And then any content will do. Right.

Critical race theory slam, right. Trans kids athletes slam right. But the same is so it’s radicalization by feeling first and the content is in its service. And that is what I’m trying to get people to notice is it’s a kind of, this is what I mean when I say it’s under the radar. It’s not totally evident.

Like we we need to be emphasizing a kind of pedagogy, a teaching of critical feeling as much as critical thinking. We’re all about critical thinking. How do the ideas? Let’s deconstruct the ideas. Let’s critique those, get better information. But we also need to ask, how did the feeling get here? How is my body susceptible to this feeling?

JM: Yeah.

KLA: Where did the feeling come from? Whose interests are the feelings serve? Right. And so it’s that kind of that line of listen to me thinking around feeling that I am advocating. We don’t to enough of it and we don’t have a public conversation about it.

JM: No. And that’s probably a gender thing as well, isn’t it. Like it’s emotions and feelings aren’t very masculine are they? But it is so interesting to hear you speak because it’s like the feeling and the emotion primes the body to be receptive to these ideas and then the body. Then we embody these ideas because of the feeling.

KLA: Yes.

JM: I kind of don’t want to go to talking about individuals now because of everything we’ve said, but we are having this conversation now because of US election and this, these ideas are so present in what we see. I’m thinking Elon Musk jumping about on stage with Donald Trump the other day, and JD Vance in particular, is emerging as this key player in the manosphere, like you said just now.

So how do these people represent what you’re talking about? Maybe just JD Vance. I was interested when you said earlier, like, watch him speak. Can you talk a bit more about that?

KLA: Yes. It’s funny that there’s a small section devoted to JD Vance in the book from two years ago, before he was anybody really to write home about because he really is like the embodiment of aggrieved manhood hijacking class. Right. And like putting a populist sort of face on.

JM: Yeah.

KLA: In the service of manly grievance there is right now a great piece, very accessible. Ben Burgess, wrote this piece about, if you listen to JD Vance and who he claims his quote unquote intellectual influences are if you watch his style, you will realize that JD Vance is reared on the manosphere, and his faux populism does not come from his experiences in Kentucky or Ohio.

And they are not about those people experiencing those things either. Right. So he kind of does a nice job of tracing this in two pages. Which is nicely accessible. But JD Vance, I think one needs to notice in both what he says and in the kind of style of saying it, both are worth noticing. So let’s take one example that became quite the furore in the US.

The childless cat ladies phenomenon. One of the things that JD Vance has been saying for quite some time is this kind of anti-feminist line that it’s women out there having careers instead of kids. That is part of the problem. Birth decline, birth rate declines, right? Like we need to care about families and people who really have a stake in the future.

This this is the sort of thinking that he echoes, that thinking which the childless cat lady remark is one of hundreds he has made to this effect that thinking comes directly from what is now, I think, fairly widely understood as so-called replacement theory. Replacement theory is a very far right notion, white supremacist notion, that in many places the white, predominantly white voting populace is beginning to turn brown for various reasons.

Right. And that this is a threat to white societies everywhere. And many people will recognize the naked racism, anti-Semitism, all these things in there, but they do not recognize the ways in which sexism and heterosexism are super important to that. According to replacement theory it’s white women falling down on their breeding responsibilities that have gotten us into this situation childless cat lady’s direct line to that thought.

That is one example of how you can hear the manosphere speaking through JD Vance. And I love how you started the question by saying you really want to talk about individuals, but we can use this as an opportunity to talk about individuals in a new way that JD Vance is channeling. He is a vessel for a much larger network of feeling in which the return of a very specific form of white, male, straight Western patriarchy is the agenda.

That’s the agenda. So you can sort of see that in the way that he the contents of what he is saying. But you can also watch the style, even the style that he exhibited at the debate, which is, if anybody did not watch it. And I bet that’s many most people, people were commenting on how he seemed so polished and so confident, what he also seemed, if you watched his body language was rocking side to side and this sort of okay.

And it was a barrage of sort of pseudo scientific sounding, quote unquote facts and figures. This is a style in the manosphere that you cannot take up with any one thing. It is basically a barfing out of information that is not actual information, but has the sound of science, the sound of intellectual debate, the sound of polish, and the idea is to get as much out there as possible that you have basically, like exhausted the opponents.

It’s a gaming tactic. It’s a gaming tactic, right? And you can watch him experiencing the thrill of that gaming tactic. So that’s kind of how I would I would, in a nutshell, kind of characterize the way in which he embodies both the feeling and the content, the style, the aesthetic, and that is his the playground on which JD Vance was made.

Now, there is, of course, a direct connection between JD Vance and all of the kind of tech billionaires and tech bros who are who not only funded him. Peter Thiel made his political career possible, but there is also an increasing turn toward aggrieved manhood within large segments of that group. So you might have, for instance, caught the Washington Post’s new, exposé on Mark Zuckerberg’s broification, and his obsession with, like, Caesar and Romans, Elon Musk.

Yep. So this is kind of the work I’m beginning to do now is to kind of trace some of the on off line networks, and particularly among tech bros, tech billionaires, how we can sort of see this as mapping a larger network of feeling that now, increasingly, I mean, it’s it’s getting to the point where, like the funding is beyond it’s just beyond rapport.

JM: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. When we worked before, when the book was first published, we talked a lot about this idea of once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

KLA: Yes.

JM: Yeah. And it’s quite terrifying. It’s permeating everything isn’t it. And it’s kind of unbelievable that it’s not talked about more. It’s so masculine.

KLA: I think it is increasingly marked like you opened this conversation with major networks in the US saying, okay, masculinity is a central issue, right? And I also think people are increasingly marking something else, that there was the Guardian piece about the Austrian far right’s recent victory that said, we need to stop looking for local reasons and start looking at the global flow of.

Right. So so you have people sort of on the edges of this, some people saying, hey, wait, we need to look at the far right online. Yeah. Which is the manosphere, okay. And we need to be dealing with gender but not connecting these two things. Right. Not connecting anytime that genders mentioned it’s like, notice this, but it doesn’t explain anything.

Nobody is sure where to go with it. It’s all focused on like hyper masculinity and these particular men who are doing this thing, but nobody seems to be in a sustained way talking about the global network of hyper masculinity that is giving the far right it’s energy around the world like that. Those are the dots I would love to see connected.

And there’s many ways journalists could do this in basic practice.

JM: So I suppose what we’re talking about now is this like, how on earth is this ever going to stop and how well, it’s never gonna stop, is it? but how do we address it and how do we think about it differently?

KLA: Yeah, yeah.

JM: And yeah, by zoning in on the role of feelings and emotions is is the way forward through that. You also talk about something called lateral empathy in the book. Could you speak to that a little bit?

KLA: Sure. At the moment I think we have two dominant ways of responding to aggrieved manhood. And one is to oppose it, cancel it, argue with it, you know, resist it in some way. And the other is to empathize with it. Right. So you think about, like I used to use Arlie Hochschild’s book as an example of this ‘Strangers in their own land’.

They crossed the empathy wall. Why would people feel this way? What reasons do they have? Right. So, like empathizing with their position and where they stand. And I’m suggesting that both of those responses, opposition and empathy, provide oxygen to this fire. They just help the virality grow. What I advocate is something that is an alternative, which would be empathy from the side or what I call lateral empathy, where I am not.

Let’s say that I’m talking to a nephew who is telling me how much he loves Andrew Tate. And I am neither saying I get it. Yeah, your friends love it. I empathize and I’m not arguing with him about like, that’s false. Did you know this? This is misinformation. But I am instead engaging with him at the level of feeling, right.

Like, how did this where where were you when you first encountered this? What did that feel like? How did it arrive? What happens to your body when you feel this way? What does it lead you to want to do? What does it draw you to? Right. So it’s like addressing like this is the term I used earlier bracket what it says to focus on how it spreads.

You know, you’re following the feeling and kind of not listening to it, not listening to all its bravado and bluster, not taking that bait, but instead addressing the feeling head on, if that makes sense. And so, I call this empathy from the side or lateral empathy and a way, you know, the way I’m trying to work with the concept of viral masculinity is, to use a pandemic metaphor that is really more than a metaphor because we are dealing with the physical transmission of feeling here.

But lateral empathy is a pandemic approach. Basically. Like you would not say back in the Covid days, oh my gosh, you got Covid. How bad? You know, like you’re awful. Like you wouldn’t, right. You wouldn’t do that and you wouldn’t sit there saying, like showing all of this like care about your symptoms. You’re like, you’re just trying to what do we say?

Slow the spread, right? Flatten the curve.

JM: Yeah.

KLA: We’re trying to cut the circuits of transmission or interrupt the circuits. And I’m suggesting that that is a better model for thinking about viral feeling is how is it flowing from body to body? What can we do to help those bodies deal with the overwhelming flow that they’re encountering? Right. How can we expose that flow and sort of pull aside the content that is keeping us from seeing it?

Right? So this is what I mean by empathy from the side addressing at the level of feeling the flow of the far right around the world.

JM: And actually that helps us understand it, like in a big picture way, and kind of see how there might be ways through it. But I would have said in the last episode, I’m a parent, well, he’s now 14, my son, and there’s something really interesting there in how you have these conversations. And I have spoken to him about this kind of thing because obviously you worry about it all the time.

Like how much of it are they seeing? And I don’t definitely don’t fall on the, this is wrong. You shouldn’t believe this blah blah blah. But maybe but and I maybe I’ve like tried to empathize and kind of go, oh I don’t know. I’ve done actually it’s really hard to have these conversations, but what I haven’t done is ever said to him, how does it make you feel?

And, almost, what does it mean to you? You have these conversations and you talk about them as if they’re outside of him, outside of us. But it’s really interesting to think how those conversations would go if you really brought it in to like him. Yeah, maybe.

KLA: What happens when you when YouTube feeds you, like progressively violent content? How’s it feel, you know.

JM: And this goes back to your thing of, like, we focus on the content.

KLA: Yeah.

JM: And we talk about the content. Right? We don’t talk about what it does to us and our bodies and Yes. Yeah.

KLA: Yes.

JM: Yes. That’s it.

KLA: Yes. So I’m trying to if I, if I could summarize as like the impulse here is to change the register of the conversation, you know.

JM: Yeah. You’ve been saying this all the way through and. Yeah, yeah.

KLA: Instead of taking at face value the content of what we’re talking about, get at what is animating the content?

JM: Got ya. Yeah, yeah. And how would that and I suppose having that kind the conversation would then change his perspective on it.

KLA: It invites you to notice. It invites him to notice.

JM: Not to turn this into a parenting lesson for me. But it’s helpful to have that kind of clear example. Yeah.

KLA: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I’ve like I in my, there’s there’s interpersonal applications for this in fraught political relationships everywhere. My own family is full of these right. So there is this has affected the way that I approach hard political conversations in my family. There’s educational ramifications of this. There’s journalistic ram- There’s so many points of intervention that I’m kind of uniting under the umbrella of critical feeling, but it can be enormously empowering and something of a relief to just drop the battle and talk right to the feeling.

So when my when I see, for example, in conversations with my own father, the intensification occurring and both of us puffing up. I can deflate, I can surrender and say, phew I am, not at ease when we talk like this. Are you okay?

JM: So that’s, that’s you dropping the aggrieved manhood isn’t it.

KLA: Yeah, yeah. This is me. Yes. Dropping my alt right. I am not at ease. When we talk, I feel like we’re talking about something else. What do you lose, dad? What do you lose? If somebody like me has an equal shot at things? Tell me about that. What are you losing? What are you trying to protect here?

What feels so, we have had stunning conversations out of that turn to address the feeling and drop bypass all of this sort of culture war flashpoints that want us increasingly barbing one another. Right? So there’s a real intervention and polarization here as well.

JM: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Oh, it’s so interesting. It’s absolutely fascinating. And it’s, it’s so. Yeah, yeah, I think I’ve got a lot to go and think about now. Again. I wanted to ask you just before we left and you talked very, very briefly about it earlier, but what, it’s two years on from the publication of Wrong and Dangerous, so what are you working on now and what are your plans for the future?

KLA: Thank you. First, I’ve been working on giving some flesh to this notion of critical feeling. And its many applications. And so I’ve been doing, actually I’ve done workshops with women in tech who are encountering this constantly in their everyday occupational lives. So just thinking of the different kind of contact points and maybe levers where critical feeling can be a meaningful intervention.

I am also keenly and increasingly interested, as I mentioned earlier, in the role of tech. I’ve just done a lot of kind of industry work with tech in particular, given my organizational and occupational scholar self. And so tech masculinities, and what is happening with things we mentioned earlier. Right now in a network sense, I’m really interested in that and kind of trying to, also figure out the relationship between that and crypto, the feeling around crypto, which I think is also caught up in this trade of aggrieved manhood.

So those are some things, I’m also always interested in, in part for personal and scholarly reasons, in the role that women play in the spread of this feeling and the role that they could play in interrupting the circuits. As I said earlier. So those are some projects I’ve also been working. This is not going away. And so while the issue is not going away, I’m engaged.

JM: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. well, I’m looking forward to reading whatever you write next. Thank you. Karen, that’s it’s absolutely fascinating and terrifying, but I love that there’s kind of there’s a few ways forward and a few shifts in thinking. Yeah, that would be really useful. So ‘Wronged and Dangerous: Viral Masculinity and the Populist Pandemic’ by Karen Lee Ashcraft is published by Bristol University Press and is available on our website, which is bristoluniversitypress.co.uk.

You can get 25% of all our books by signing up to our mailing list. And finally, thank you for listening. If you’ve enjoyed this, please follow us wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you. Thank you again, Karen. That was awesome.

KLA: Thank you. A delight.