The battle for and against AI is starting to feel like a war. Tech proponents argue it will transform everyone’s lives into a leisure-filled paradise while opponents anticipate a savage world defined by a brutal inequality between AI masters and its slaves. So polarised a debate repels reasonable people who might prefer to hide, but the reality is that its outcome will change our lives. Just not in the way you might think.

Ever since ChatGPT bounced onto the scene, writers, musicians and visual artists have had to come face to face with the reality that this new technology acquires its ‘intelligence’ by scraping their work. This means several things:

- The gigantic value generated by AI companies owes a huge amount to work done by others who are being paid nothing.

- Copyright protection exists the minute a musician, writer or artist produces a work; no formalities are required. This makes it a beautifully easy system to enforce. But AI flouts that law each time it scrapes an artist’s work; it’s like automating shoplifting.

- Artists’ ability to earn income from their work is threatened by AI’s capacity to generate a limitless number of derivative works. When the scriptwriter Alison Hume found that the subtitles of her TV scripts had been scraped, she knew they can now be used to generate scripts without her. Her legal rights have been violated, her future earnings threatened, and the BBC can’t protect work they paid for.

Since the advent of AI, artists have seen jobs evaporate. In music, the writing of jingles for commercials – the classic entry-level job for young musicians – has been automated almost overnight, while the number of jobs creating images fell by 35 per cent in just seven months.

Not surprisingly, artists are up in arms. The government consultation proposes three options:

- Doing nothing;

- Strengthening copyright, requiring licences in all cases;

- Allowing artists to opt out of their work being used for AI.

Doing nothing is not an option. Current copyright law is inadequate and the courts are swarming with lawsuits. Opting out turns copyright law on its head, requiring artists to protect each work every time they make one. It replaces an easy, elegant system with a bureaucratic process with no workable means of implementation or enforcement. The choice should be simple: strengthen copyright law to provide artists with fair remuneration for their work and a safe online environment where it is protected.

Instead, the government’s argument is framed by a false binary: support AI or support artists. Peter Kyle, Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology argued that it would be a disaster if ‘young people studying in colleges and universities around the country who aspire to work in technology’ should have to ‘leave the country and work abroad in order to fulfil their potential’ just because artists clung to their right to legal protection. Sure, he conceded, artists are ‘emotionally’ attached to their work – but economics matter more.

This is an absurd misrepresentation. I’ve spent my life in media and running technology businesses. The mindset which sees technology, engineering, mathematics and science as serious, disciplined and valuable but the arts as frivolous, emotional and wasteful could not be more wrong. The musician Soweto Kinch says it’s common for people to compare the arts to ‘dessert: unnecessary and probably bad for you’. But artists, scientists, and technologists themselves see this quite differently.

Artists aren’t afraid of uncertainty; they move towards it, just as scientists do, knowing that that is where new discoveries can be found. Both embrace work that is risky, challenging and unpredictable, undaunted by complexity or ambiguity because that’s where breakthroughs happen. These qualities are fundamental to all innovation. Artists are some of the most disciplined, tough, courageous, insightful, fearless, and resilient people in our society. They start work before being asked, show initiative and don’t quit when it gets hard. Driven by curiosity, they develop whatever new skills a new project demands. Trained to be self-critical, they are both imaginative and analytical.

Now look at the 2023 World Economic Forum Future of Jobs Report: The most essential skills for workers? Analytical and creative thinking. In 2024, employers told Forbes that creative thinking is the most in-demand skill. The National Foundation for Educational Research, studying ‘essential employment skills’, anticipated the skills most sought by employers in the future to be: communication, collaboration, problem-solving, organising and prioritising work, and creative thinking. These are skills artists deploy all the time – and that making art, of any kind at any level, develops in us all. We need the whole ecosystem of the arts – the teachers, the libraries, the museums and concert halls – to keep them alive and growing in our society if it is to have the resilience and innovative capacity the future demands.

Yet working with CEOs of global businesses, what I hear about the young, aspiring workforce is dismaying. ‘We hire well-credentialed people, from good schools and universities, who are fine at doing what they are told. But when we need creative thinking, they’re lost. It isn’t what they’ve learned. I’m not sure what we’ll do with them when they’re 35.’ The frustration is palpable.

This is what happens when you cut arts and humanities out of the education system. When you denigrate it as ‘emotional’, inessential, soft. When you instigate criterion-based assessment, grading an essay according to how closely it approximates to the ‘model’ answer. When you penalise students for imaginative responses to banal assignments. You lose creativity just at the moment it is needed most. That is the biggest economic and human rights failure the UK faces now.

Art is good for us. For young people, daily reading, dance, music or art lessons reduce hyperactivity and inattention and develop empathy. For adults, participation in the arts is associated with less mental distress and happier lives – independent of background, income, medical history, demographics or personality. For the elderly, more involvement in the arts makes them feel better, with fewer long and chronic diseases, a lower rate of depressive symptoms and obesity. And if all that is too emotional, in the year September 2021–22, while the British economy grew at the rate of just 1.2 per cent, the creative industries grew 6.9 per cent. Imagine: an industry loved by buyers and sellers alike, that benefits all other industries as well as society as a whole.

The truth about AI and the arts is not binary. We need both: well funded but, even better, well understood. In an age of uncertainty, transforming society requires more intelligence, not less.

Margaret Heffernan worked for 13 years as a radio and television drama and documentary producer. She then spent eight years in the US running media technology companies and was named one of the internet’s Top 100 by Silicon Alley Reporter and one of the Top 100 Media Executives by The Hollywood Reporter. She is the author of six books and her TED talks have been seen by over 15 million people.

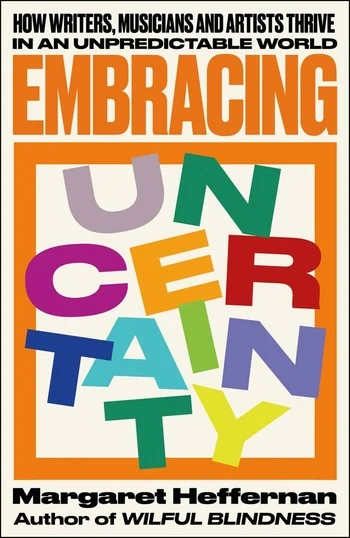

Embracing Uncertainty by Margaret Heffernan is available to purchase on Bristol University Press for £12.99 here.

Embracing Uncertainty by Margaret Heffernan is available to purchase on Bristol University Press for £12.99 here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Bristol University Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Marija Zaric via Unsplash