Three and a half years after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the war relentlessly continues. Negotiations between Russia and Ukraine have stalled, Kyiv conducts drone strikes deeper and deeper into enemy territory, and Moscow makes steady territorial gains in Ukraine’s East, with the southern frontline only 35 kilometres from Zaporizhzhia – a major Ukrainian city that was one of my locations for research fieldwork. The focus of much analysis of the war has been on military gains or, more recently, political moves towards an unlikely, dubious peace; however, crucial questions surround the political economy of Ukraine. It is vital to understand the state of Ukraine’s political economy, as it determines not only Kyiv’s ability to prosecute its defence against Russia, but also conditions the possibilities for reconstruction and peacebuilding.

How, then, is the political economy of Ukraine faring as it continues to confront Russia’s invasion?

Russian jets and Western debts

Ukraine’s history since the dissolution of the Soviet Union has been plagued by recurrent economic crises, popular revolts, war and viral epidemics. These tumultuous decades have meant that Ukraine was dependent on foreign loans long before Russia’s 2022 invasion. Since the war in Donbas erupted in 2014 up until the 2022 invasion, Ukraine borrowed substantial sums from the world’s largest international financial institutions, receiving over US$8.4bn from the World Bank and US$14.1bn from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These loans, contingent on radical neoliberal restructuring in the Ukrainian economy, also catalysed enormous amounts of debt for Kyiv.

When the 2022 Russian invasion began, the country was drowning in over US$143bn of debt (84 per cent of Gross National Income), and was expected to repay US$14bn of it in 2022. A significant proportion of this debt is owed to the major, US-based international financial institutions, the IMF and World Bank, alongside a coterie of global bondholders that includes major (vulture) hedge funds such as Aurelius Capital Management and VR Capital Group.

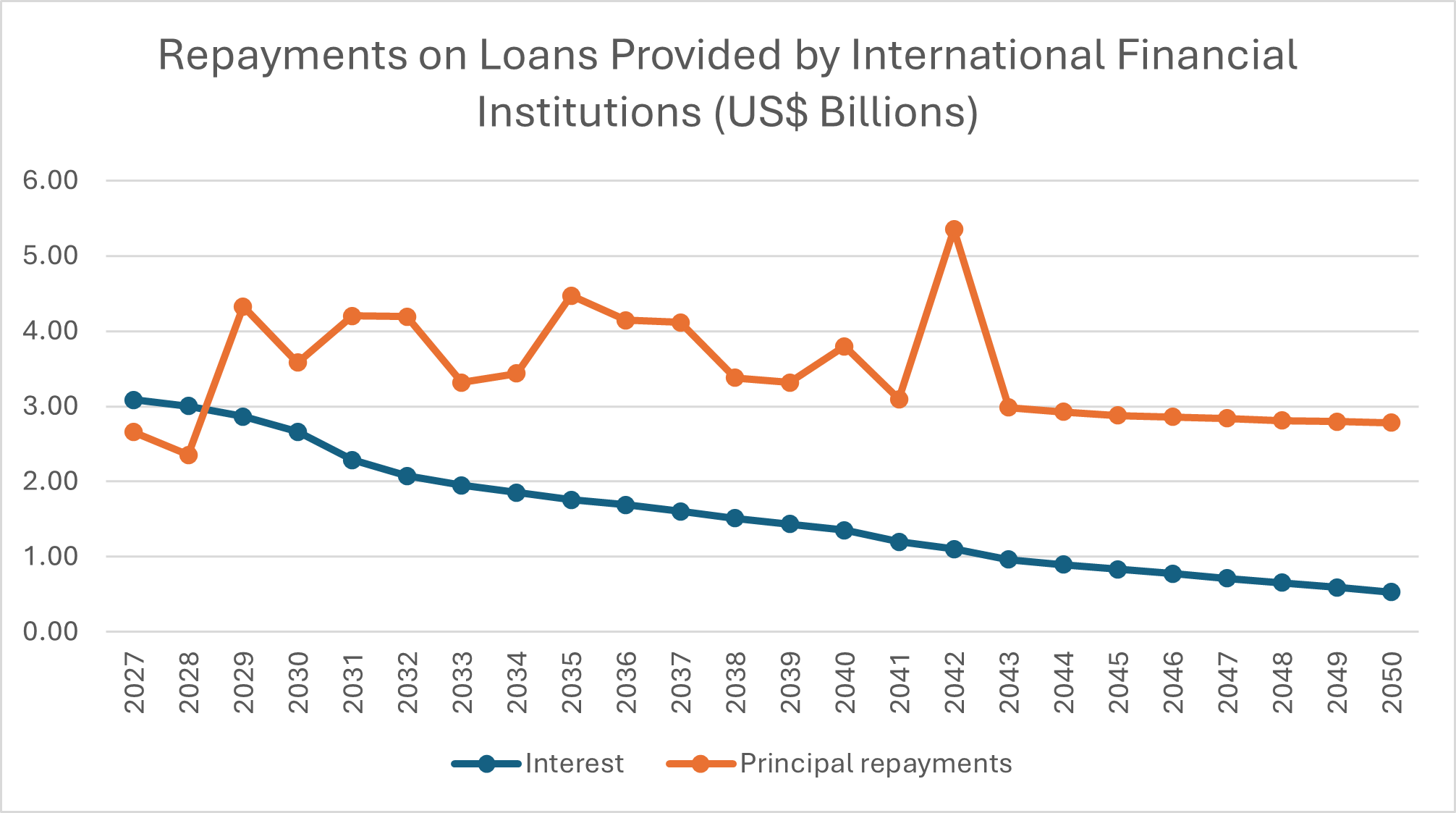

By 2025, Ukraine’s debt had exploded to over US$160bn (92 per cent of GDP), as war costs escalated alongside the imperative of securing further loans. More than US$101bn is outstanding to the international financial institutions, with over US$20bn owed to the World Bank and at least US$15bn to the IMF. The Ukrainian government estimates that it will repay these institutions US$2.4bn in principal and US$2.1bn in interest during 2025, with these extreme rates of repayment projected to continue for at least 25 more years. These figures dwarf Ukraine’s expenditures on vital sectors such as environmental protection and education. The World Bank and IMF have so far refused to forgive any of the debt Ukraine owes, which has flown in the face of the international solidarity their most powerful state shareholders professed to have (the US and EU).

Besides the international financial institutions, Ukraine has faced a constant battle on the ‘western front’ to renegotiate its debt held by Western bondholders and other creditors, receiving fleeting relief in 2022 and 2024. However, the patience of debtholders appears to have evaporated. In April, the Ukrainian government failed to restructure over US$2.5bn of debt, defaulting on its regular repayments as the economic crisis struck a crippling blow. This debt concerned ‘GDP warrants’, which Ukraine sold to investors in 2015 amid another economic crisis – basically, these instruments trigger handsome payouts from Kyiv’s coffers to investors once Ukraine’s GDP growth meets a certain threshold. Because of the drastic GDP drop with Russia’s invasion in 2022, there was an inflated ‘growth’ in 2023–2024, as international financial support arrived and the country staved off total collapse. This meant huge repayments were due to international creditors holding ‘GDP warrants’, which Ukraine was unable to meet.

De-risking the war for international capital

Ukraine’s debt situation evinces a collapsing political economy, as the war-weary state struggles to meet the demands of international creditors, including the World Bank and IMF. Importantly, Kyiv’s debt repayments exceed expenditure on crucial sectors. Purely interest payments on debt due (US$11.5bn) is more than that spent on pensions and social programmes (US$10.2bn), which suggests the obscene burden of debt owed to international ‘allies’ is crowding out vital funding for the conflict-affected populace.

Because Ukraine is unable to access international lending markets due to its default, it must turn yet again to the World Bank and IMF for financial support. This will mean not only more debt, but these institutions will demand conditions on their loans that ensure Ukraine ‘de-risks’ the war environment for investors, to guarantee their profits, while de-prioritising the struggles and survival of everyday Ukrainians. This has been the pattern throughout the war in Donbas, where both the World Bank and IMF demanded radical restructuring to protect the profits of business, over and above concerns of ordinary, conflict-affected Ukrainians, with their economic restructuring programmes often negatively and disproportionately impacting vulnerable groups.

This pattern is set to deepen. The International Finance Corporation (IFC), the ‘private arm’ of the World Bank, has embedded itself in Ukraine, becoming the country’s ‘strategic advisor’ in reconstruction. It is not the World Bank’s sub-groups that address poverty and development that are leading lending to Ukraine, but the IFC, which focuses on supporting international and national business, with little to no requirements that ensure benefits for conflict-affected Ukrainians. The IFC has been highly active in the last two years, providing guarantees and other de-risking instruments for private business operating in Ukraine, such as US$217.5m for investors led by a French billionaire to monopolise a Ukrainian telecom, over US$360m of de-risking facilities for corporates in Ukraine, US$130m to giant agri-business MHP, millions for equity funds operating in the war-ravaged country, and driving public-private partnerships that funnel taxpayer money to private capital.

After three years of war, Ukraine needs US$524bn to rebuild, and much of that money will come from the World Bank and IMF, which will demand stringent conditions to ‘de-risk’ the conflict-afflicted country for private business. Already, as Russia continues to attack Kyiv, the World Bank has over 40 requisite actions in place for Ukraine to access funding, with the IMF not far behind with 37 conditions (the EU has even far more ‘strings attached’ for its financing). Both these international financial institutions are readying more loans to Ukraine, which will occasion even more debt, as broader global actors demand that Ukraine be ‘de-risked’ so that its vast resources, including critical and strategic minerals, are made safe for capitalism. However, as has been the case since 2014, the war-affected populace has yet again been ignored, which is a recipe for further immiseration, destabilisation and violence.

Elliot Thomas is an early career researcher and Lecturer in the Faculty of Law at Monash University.

Making War Safe for Capitalism by Elliot Dolan-Evans is available on Bristol University Press for £85.00 here.

Making War Safe for Capitalism by Elliot Dolan-Evans is available on Bristol University Press for £85.00 here.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Jon Tyson via Unsplash