On 14 May, the majority of voters in Turkey will vote against Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) for its economic mismanagement, corruption, human rights violations and catastrophically ineffective response to the 6 February earthquake that left 50,000 people dead and more than 100,000 wounded – a consequence of political choices made over two decades of continuous rule.

After 21 years, there is finally a good chance that Erdoğan’s AKP will lose its majority in parliament, and will no longer form the government.

The main reason for AKP’s decline has been its inability to deal with Turkey’s most pressing problems, coupled with its leaders’ mediocrity and arrogance. But opposition parties have also got smarter this time around and are running an effective political campaign. They formed two electoral alliances to increase their seats in parliament, and support a common presidential candidate, Republican People’s Party (CHP) leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, who is expected to win against Erdoğan – if not on 14 May, then in the run-offs two weeks later.

Turkey’s elections are not exactly free or fair. Having control over 90 per cent of media and public coffers, Erdoğan and cronies deny opposition parties airtime. On 25 April, 126 politicians, lawyers and journalists were taken into custody.

Despite these serious obstacles, the opposition draws big crowds to its rallies, and leads an effective campaign that is positive in content and tone. From his kitchen, study or living room, Kılıçdaroğlu explains how his policies address people’s everyday problems such as food, electricity and housing costs. Linking rising poverty and inequality to AKP’s policies, he talks about his plans: basic income support, the elimination of corrupt hiring practices and more. In contrast to AKP’s sectarianism, Kılıçdaroğlu owns his Alevi identity, upholds shared values over divisions, and speaks of diversity and reconciliation (using the Islamic concept of helalleşme).

By contrast, the Erdoğan campaign bombards the public with videos featuring glossy phallic metal objects such as oil rigs, fast trains, planes and aircraft carriers that promise economic prosperity. Its emotive videos feature soldiers who would have been killed were it not for Türkiye’s ‘local and national defense industry’, while their worried mothers and sisters (filmed cooking and talking in the kitchen) promise gendered visions of security and stability.

Otherwise, Erdoğan’s campaign is a negative one. He accuses the opposition of being a ‘Trojan horse for imperialists’, supported by ‘the terrorists’ or being terrorists. Anti-LGBTI+ rhetoric and hate speech feature heavily. With fascists long in Erdoğan’s camp, and now two reactionary Islamist parties added to the fold, the alliance is a haters’ alliance. No wonder his supporters attack opposition rallies.

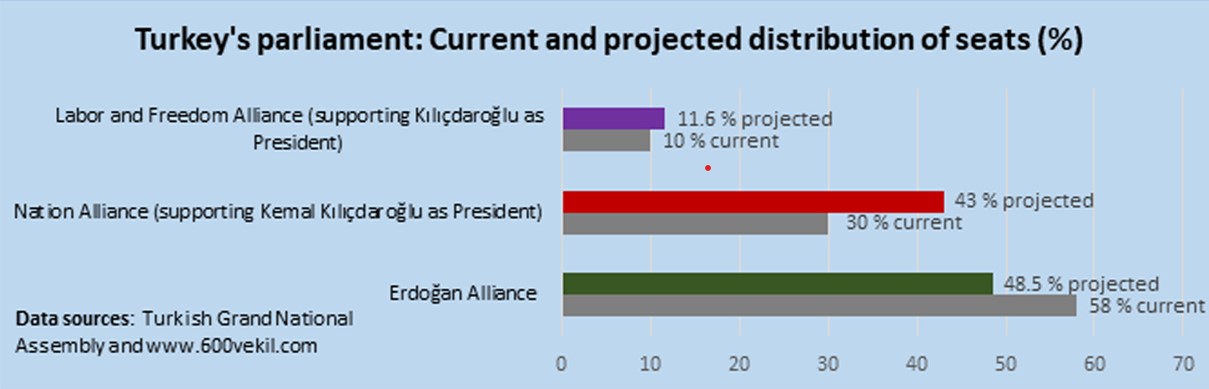

Sadly, over 30 per cent of voters will select Erdoğan no matter what. Despite AKP’s loss of support and the likely loss of its majority, it will probably still be the biggest party in parliament.

The politics of gender and the future of democracy

This most critical election in Turkey’s 100-year history is fundamentally about two very different visions of society, and the politics of gender is not incidental, but intrinsic to them.

The opposition’s vision is basic but also radical in the current context: a political system based on the rule of law and respect for human rights. Certainly, political parties making up the opposition are ideologically diverse, and do not always live up to the principles they espouse. Nevertheless, representing millions who suffer authoritarian rule, the opposition understands what it means to be censored, fired, jailed or killed for dissenting. All (except the Saadet Party) publicly vow to return to the Istanbul Convention, from which Turkey withdrew in March 2021 despite its ratification in March 2012 by a unanimous vote in Turkey’s parliament. This return is a key focus of struggle for feminists in Turkey.

Erdoğan’s vision for Turkey offers more of the same gender-based (and other) violence and one-man rule.

His electoral alliance includes HÜDA-PAR (‘Party of God’), the political wing of Turkey’s Hezbollah, responsible for the brutal torture and murder of Muslim feminist Konca Kuriş, among others.

Erdoğan and his followers promise mini-Erdoğans that they will be ‘chiefs’ in their own spheres, starting within the family. This is a vision of society that is shaped by ‘religion’ – more precisely, patriarchal and misogynistic interpretations of Islam. Hence the discourse of ‘protecting the family’. In the context of high living costs coupled with a lack of secure and well-paid jobs, the promise that at least they will be ‘in control’ of the women in their family may appeal to men (and some women). Never mind that this idealised and fantastical notion of the family sits in stark contrast to the reality of gender-based violence against women, committed mostly by husbands, ex-husbands and other male family members – not to mention the abuse of children.

In December 2022, AKP proposed an amendment to the constitution, putatively to guarantee women’s rights to wear headscarves and to prevent LGBTI+ marriages. In reality, this was a political move to rekindle past grievances over headscarf bans and to feed anti-LGBTI+ propaganda. Kickstarting its election campaign while claiming to ‘secure’ a freedom, AKP tried to give the state expansive powers to dictate dress code for women against two foundational principles of the Republic: equality and secularism.

Erdoğan’s haters’ alliance wants men to be in control. They want chiefs in the family, chiefs in society and a head chief for the state. They do not want women to exercise their right to abortion or birth control. They want to lower the minimum age for marriage so girls can be married when they reach puberty. They claim that being gay ‘brings disease’ and that LGBTI+ ‘propaganda’ and organisations must be banned. They juxtapose the ‘protection of the family’ and LGBTI+ existence and organisations, denying the obvious fact that LGBTI+ people also come from and have families of their own.

Like Erdoğan himself, the parties in his alliance reject the principle of gender equality, saying they believe in ‘God-given nature’ (fitrat) instead. They consider women’s primary job to be motherhood, and work outside the home – and women living alone – an aberration. They want to ensure that men rule while women obey and stay in the shadows. They want no reality – certainly not women’s and LGBTI+ people’s will to exist as they want to exist – to complicate their reactionary heteronormative fantasies.

That the politics of gender is vital in the election of the century can be seen in HÜDA-PAR and YRP’s stated goals: repeal the national domestic violence law, recriminalise adultery and institute sex-segregation in education. They want to prevent ‘perversions such as drug addiction, deism, atheism, and homosexuality’. They seek to further restrict alimony rights, which courts typically afford divorced women in need (albeit in woefully minimal amounts). Having successfully attacked the Istanbul Convention, these Islamist parties now want Turkey to leave international human rights treaties such as CEDAW and the Lanzarote Convention, which is to say they want more freedom to discriminate against women, and exploit and abuse children.

Even if the opposition wins on 14 May, there will still be too many misogynists and too few women in Turkey’s parliament.

No political party – except for HDP and TİP of the leftist alliance – has come close to ensuring women’s equal representation. Feminists will continue to struggle, mostly outside parliament, for their most basic human rights to ensure that gender-based violence does not go unpunished and that survivors have legal recourse and social protections; to keep the minimum age of marriage at 18; and to prevent the amnesty for sexual abusers of children that AKP tried to pass in 2016, and then again in 2020.

Given that Erdoğan – like Bolsanaro, Orban, Putin, Modi and Trump – is a symbol of authoritarianism and the decline of democracy, the upcoming election has international implications. It also has implications for US and European security policies, Russia’s war on Ukraine and NATO’s expansion.

The ‘election of the century’ is about choosing between a ‘Turkish-style’ presidential system inaugurated by Erdoğan (where whatever he says goes) or a parliamentary system based on the rule of law, a minimum necessary condition for any democracy deserving of the name.

All that said, we cannot talk about security or democracy without paying attention to the politics of gender that shape people’s lives and livelihoods. The 14 May election is fundamentally about which societal vision will prevail in Turkey, and whether people – girls, women and LGBTI+ in particular – will be able to live free from violence in a country that respects the principles of equality and secularism, and the human rights of all.

Özlem Altıok is a Principal Lecturer holding a joint appointment with Women’s and Gender Studies and International Studies at the University of North Texas and the author of the chapter ‘From the Streets to Social Policy: How to end gender-based violence against women’ in the Global Agenda for Social Justice 2.

Global Agenda for Social Justice 2 edited by Glenn W. Muschert, Kristen M. Budd, Heather Dillaway, David C. Lane, Manjusha Nair and Jason A. Smith is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £14.99. The chapter ‘From the Streets to Social Policy: How to end gender-based violence against women’ is available to buy on Bristol University Press Digital.

Global Agenda for Social Justice 2 edited by Glenn W. Muschert, Kristen M. Budd, Heather Dillaway, David C. Lane, Manjusha Nair and Jason A. Smith is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £14.99. The chapter ‘From the Streets to Social Policy: How to end gender-based violence against women’ is available to buy on Bristol University Press Digital.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Photo from video produced by Gökçeçiçek Ayata and EŞİK Ajans