Billionaires represent a scourge of economic inequality, but how do they get away with it within our culture?

In this episode of our Transforming Business podcast series with Martin Parker, Carl Rhodes, author of Stinking Rich, explains the dangerous and deceptive myths which portray billionaires as a ‘force for good’.

They discuss the myths of the heroic, generous, meritorious and vigilante billionaire, and how their wealth and power is setting us back to old-fashioned feudalism and plutocracy.

Hosted by leading organization studies professor Martin Parker (University of Bristol), Transforming Business is a new series from Transforming Society, featuring in-depth conversations with top experts in work, economy, finance, employment, leadership, responsible and sustainable business, innovation, organising and activism. These insightful interviews explore fresh ideas and bold strategies for creating a more ethical and equitable business world. Tune in to challenge conventions, spark innovation and drive meaningful change.

Listen to the podcast here, or on your favourite podcast platform:

Scroll down for shownotes and transcript.

Carl Rhodes is Professor of Organization Studies and Dean of the Business School, University of Technology Sydney.

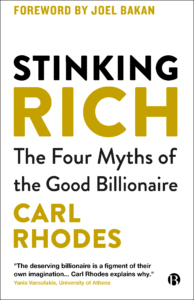

Stinking Rich by Carl Rhodes is available on Bristol University Press for £19.99 here.

Stinking Rich by Carl Rhodes is available on Bristol University Press for £19.99 here.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Ali Kokab on Unsplash

SHOWNOTES

Timestamps:

00:31 – What did you want to achieve with this book?

01:25 – Why do you think we have an elevated perception of billionaires?

05:45 – The myth of the heroic billionaire

09:51 – The myth of the generous billionaire

14:04 – The myth of the meritorious billionaire

19:20 – The myth of the vigilante billionaire

26:30 – The importance of writing for a non-academic audience

Transcript:

(Please note this transcript is autogenerated and may have minor inaccuracies.)

Martin Parker: Hello, my name is Martin Parker. I’m professor of organisation studies at the University of Bristol Business School. It’s my huge pleasure to welcome my friend Carl Rhodes, who has written a really splendid book for Bristol University Press entitled ‘Stinking Rich: The Four Myths of the Good Billionaire’. Thanks ever so much for coming on, Carl.

Carl Rhodes: Great to be here, Martin, great to talk to you.

MP: Lovely. Well, we’ll have half an hour’s natter about the book then. So can we just start off with you kind of summarizing in a couple of sentences, I suppose, what you think the book is doing. What did you want to achieve with this?

CR: Well, well, I was interested in this phenomena of billionaires and inequality and the injustice it represented. And I wanted to know how did they get away with it? Not how do they get away with it financially, but how do they get away with it culturally? You know, why is it that many people, you know, think of billionaires as kind of great heroes and role models?

Well, in fact, to my mind, they represent a whole system of global inequality that’s getting worse. And that that causes suffering for many people. So that’s, you know, culturally, how do they manage to do that? And so I came up with this idea of the the myths of the billionaire. What myths enable them to be seen as, in many cases a force for good, to use an expression that’s sometimes used.

MP: It is an astonishing comm trick in a sense, isn’t it? In that we have now a situation where a small number of people seem to be maybe richer than anybody ever has been. I don’t know whether you could calculate that, but we are being convinced that these people are cleverer than us, are wiser than us, are capable of running our world and making decisions about us. Why do you think this is happening?

CR: I think we’ll kind of reach, I mean, it hasn’t happened overnight. You know, it’s been a long period and there have been other periods in history of extreme wealth, you particularly think of the robber barons, you know, the late 19th, early 20th century, but it is more extreme now. And I think you’ve got to put it on a historical trajectory, kind of starting, in the 70s and 80s around the neoliberal era that we’re in.

And this was, you know, obviously a time where business itself became, quite heroic. And we saw deregulation and trickle down economics and reduction of taxes, taxes on the rich, and a whole kind of revaluing of, of, the role of commerce, which promised, you know, you might remember Margaret Thatcher’s popular capitalism, right, which promised that everyone would prosper.

But of course, that was the original con of trickle down economics, if you want to call it that. And it hadn’t, it created a system of growing and growing inequality. And that’s just kind of continued to go. And again, culturally, these things were, were seen, as, you know, the valuing of entrepreneurship and rich people as being self-made, which is obviously nonsense.

So I think we’ve been on a trajectory for some 40 odd years that’s got us into this mess where inequality has has broadened largely as a result, not of, you know, the the wonderful entrepreneurial skills of of the people who became wealthy. I mean, this is a policy mistake. This is a government policy error that has created this situation, no matter how much, you know, people, rich people want to claim to be self-made.

They’ve just taken advantage of a system that enabled them to do that.

MP: Yeah. So the idea of individual heroism doesn’t really work terribly well in that kind of context, does it? I was just thinking then I’ve known your work, been following your work for quite a long time. And this this kind of builds on a sense of outrage that you’ve had for a long time about the activities of corporations, particularly around corporate social responsibility.

And your previous book for Bristol University Press, which was called ‘Woke Capitalism’, also attracted quite a lot of notice in terms of that sort of insistence on puncturing certain kind of bubbles. Yeah. So a sort of self-righteousness in a way, about the kind of entrepreneurial or managerial elite or something like that, the way that they present themselves. You seem to find that a particularly offensive position.

CR: Yeah, I suppose I do. I hadn’t really thought of it in that way. I mean, I think there’s a kind of iconoclasm to the to the approach that I take as well. But more than anything, I don’t know about self-righteousness, but more about a concern for justice and a concern for justice as the basis of a decent society or even, you know, beyond a particular, particular society.

And I think I’ve always had a strong sense of that, and that certainly informed my work, especially now, where we see economic injustice just becoming, you know, ridiculous. I mean, the number of billionaires just continues to expand. There was a report released, recently by Oxfam and they showed that in 2024, one year alone, the wealth of billionaires grew by $2 trillion.

And that was a 15% increase. That’s just kind of insane. You know, we’re on track to have 5 trillionaires in the next ten years. Elon Musk like, you know, suggesting will be the first. So you have this massive injustice. Yeah. That kind of bothers me and inspires me to think and write and and in a sense to try and create some greater or contribute to a greater public debate around these issues.

MP: Yeah. And in a sense what’s I mean, I share your concerns in a sense. What’s amazing is that you should have to write a book like this because the injustice is so clear, isn’t it? And that’s, that’s when we get into the kind of the, the sort of the center of the book, really, what you call the four myths that support the idea that the rich are somehow righteous.

Yeah, that they deserve what they’ve got. And they provide a kind of blessing for us in a sense. So should we just move through those? And then you can talk about each one of those as we go. So the first one you talk about is the idea of the myth of the heroic billionaire. Could you summarize what you’re doing in that one?

CR: Yeah. I mean, particularly here. Well, I use the term heroic in relation specifically to the American dream and the globalisation of the American Dream, not just limited to the United States. And the idea here is that the billionaire is some kind of heroic protagonist of this story of, you know, everyone can succeed, but in fact, this is more a story of kind of, I don’t know, it’s a kind of a cruel version of survival of the fittest social Darwinism.

And so the rich then if you believe in the American dream where everyone can be successful, the people who are successful isn’t that great for them. And we see the kind of the globalisation of this American dream through the process of neoliberalism itself. But what you’ve got to bear in mind, the original American Dream, the idea of the American Dream was an idea that came from a, a man called James Truslow Adams, and he wrote a bestselling book in 1931 called The Epic of America.

And he wanted to look at what is the kind of character of the everyday, normal American. And he saw America, as many have, as being a promise of freedom and independence, where people you know from a kind of class, addled Europe could, could arrive in a new country and everybody could be successful. And so this was the promise, of America for many people.

I mean, largely white people, of course. But what we see today in the New American Dream, as I call it, is not that that everyone can be successful is that anyone can be successful, but only few will be. And these few people, you know, measured by wealth are the billionaires. And if you’re not a person who’s successful, it’s your own fault, and to use a term that Donald Trump likes to use, if you’re not successful, you’re a loser, take responsibility for it.

And therefore the billionaires are the heroes, rather than being seen what I would see they’re just a side effect of of a failed system, which isn’t a system of shared prosperity, it’s a system of inequality. But we’re led to believe that they’re the heroes of this American dream, and we should all try and emulate them. And, you know, you and I, too can become billionaires.

MP: There’s an interesting echo here, isn’t there, in some kind of American culture, because there’s also in the US, I think, in US popular media, and you and I have both written a bit about this, a kind of persistent suspicion of the powerful, and of the state and of big business as well. So there’s a, there’s a curious kind of doubleness to this cultural image of the, of the hero also potentially being quite a dangerous villain.

CR: Yeah. I mean, you know, no culture is kind of monolithic. So there is there is resistance to this idea. And you see a lot of that in popular culture, although coming to American system, you didn’t see it in the, voting habits of, of Americans recently who we now have it, you know, in the US, obviously, Donald Trump himself, a billionaire presidency, his previous presidency, helping him a lot with that.

You got Elon Musk, running, the Department of Government Efficiency, the richest man in the world. But also, if you look at Trump’s administration it’s jam packed with, billionaires because these are the people who are going to make America great again, is the the myth that’s been sold. So again, we see this idea of these heroic people who are able to, solve these problems for us because they’re so great.

And not only are they so great, they’re better than you and me because they’re rich. But that’s not uncontested in the US by any means.

MP: Yeah, well, any culture contains its contradictions, as you say doesn’t it? The second one of these myths that you talk about is the idea of the generous billionaire, the billionaire philanthropist, I suppose.

CR: Yeah. And there are many, billionaire philanthropists, but here what the idea is that that, you know, billionaires are, good, righteous because they’re so generous and obviously generosity. One of the great virtues of humankind. So. And billionaires give away a lot of money probably that, you know, an interesting example, quite striking example is what’s called the Giving Pledge, which is a kind of system set up by Warren Buffett and, Bill Gates.

And it’s been around for a while. 2010 was when it was set up. And what they do is they encourage billionaires to give away all their money. And there’s hundreds of people who’ve, who’ve signed up to this. And it’s not a legal commitment. They just have to make a moral commitment to give away their money. Mark Zuckerberg’s on there.

Barron Hilton, Michael Bloomberg, Elon Musk and new people are signing up every year saying they’re going to give away all their money. And they do give away a lot of money. I mean, interestingly, they still keep making a lot of money as well. And this is part of a system that that some people these days call philanthro-capitalism and rich people.,

again, it’s based on this idea that rich people can save the world. But if you think about it, look at the Bill Gates. Well, well, if you look at the World Health Organisation, the biggest funder, and this is likely to change. But the biggest funder historically has been the United States, the third biggest funder has been, the United Kingdom, second biggest funder, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

So we have a private individual or a foundation run by private individuals who can make significant influence on world health based on their own particular preferences, without any expertise in this kind of area. And if you think of that in terms of democracy, I mean, not democracy as a political system, but democracy more as a kind of, you know, way of living or as a way of, to what right should individuals have this kind of super powers for no other reason of being rich?

And so philanthropy, on the one hand, justifies inequality because rich people are going to give away their money as if, you know, those without money somehow have to survive on the crumbs that fall from the from the master’s table. And again, it’s a kind of it’s a renewed, feudalism where wealth accrues to the powerful, a new plutocracy generated by this kind of wealth.

You know, this particular myth that I see of of how philanthropy, which is real. And I’m not saying that, you know, real people will benefit from this money. I mean, real people might also benefit if billionaires didn’t engage in tax avoidance, that would be another way. But we don’t see much, generosity exercised through the tax system from billionaires.

MP: It’s an interesting, tricky argument in a way, isn’t it? Because at the beginning and the end of your response there you kind of had to say something about the generosity of billionaires in order to question the generosity of billionaires? It’s a kind of because I suppose the easy pushback would be, you know, don’t you want Bill Gates to give away all his money or something?

And it’s that, that, that kind of thing, wouldn’t it? But you’re almost kind of trapped by the, by the system that we are part of into a certain kind of logic that encourages philanthropy as a good way of imagining redistribution.

CR: Yeah. And I think it’s also worth asking, as when anyone gives you a gift, what do they want in return? Obviously the, you know, the gift’s not without strings. So what you when billionaires give away their money, what do they want in return? And it would seem to me on the one hand, they might want power.

As you see, Bill Gates power through his giving. But what they probably also want is legitimacy. And by gaining that legitimacy that keeps the current system intact. And despite their generosity, it helps keep the system of growing inequality also intact. So it’s actually a way of making sure nothing really changes.

MP: Yeah. Nicely put. So your third one is the myth of the meritorious billionaire. Could you explain what you mean by that?

CR: Yeah. This is the idea that billionaires are wealthy because of the basis of their own merit. You know, they are self-made men, or the vast majority are men and, I use that term generically, and therefore, because they made this money, then they deserve it, because that’s what they did. Of course, if you look at the actual source of billionaire wealth, the three main sources of billionaire wealth, monopoly power and the abuse of markets through through monopoly power often kind of taken fairly ruthlessly. Inheritance or some kind of cronyism or illegal or even potentially illegal things.

So those are the three things. But billionaires always insisting that they deserve it. Even, you know, Donald Trump, constantly saying, you know, I mean, he was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. Right? And he’ll say I was self-made. I had a small loan from my father, you know, and so you constantly get this. And it’s not that there’s some kind of family connections, inheritance or or luck, but, that it’s merit.

And I think we need to question the whole idea of, of meritocracy itself, which became a kind of culturally became talked a lot more around when Tony Blair was, prime minister of the United Kingdom. And a bit later, when Barack Obama was the president of the United States, meritocracy became a key part of political, discourse, as if meritocracy is the bedrock of democratic and capitalist societies.

And you see it coming back again. Now in the US, where talk of meritocracy is the justification for the aggressive, dismantling of, what in the US they call diversity, equity and inclusion on the basis of this meritocracy of the idea that people can, you know, just be successful based on who they are. But this, again, you know, is a, justification for billionaires.

It’s okay to be filthy rich because you deserve it. And again, as I said before, if not, you’re just, a loser. It’s not an accident of birth or result of some systemic disadvantage that you’re not rich. It’s because you’re just not not worthy. So is meritocracy as a as, a thing in the first place, a good thing anyway?

I mean, it creates this new system of inequality and why should, and even if we did have a meritocratic society, which we don’t, why should one person just because maybe they’re born with more intelligence or more aptitude or more abilities in some kind, on what basis does that justify that they should somehow have a better life? Is that any more of a justification than birthright?

As you would have seen in feudal societies, I would say no. I mean, that’s not the basis on which wealth should be distributed, but it’s positioned as it is. So this whole idea of meritocracy, which is having a resurgence at the moment, justifies billionaires. But again, helps keep things unequal.

MP: I mean, that’s you you know what you’re calling there a meritocracy is a kind of an element of the the idea of the American Dream, isn’t it? That social mobility would mean that the poor boy could become president and so on. And that’s a really important myth in the US in a way that it’s not quite the same in the UK, because the UK has such embedded ideas about social class and the transmission of privilege and so on.

CR: Yeah, I mean, it is particularly and the heroic billionaire and the meritorious one is very connected, you know related things. But it is a particular thing from the United States all the way back to the Horatio Elgar kind of stories and so forth. But I do think that this is increasingly globalized as well. And if you look at Britain, for example, while it’s different that we’ve still had the kind of the whole kind of cult of entrepreneurialism and the idea that, you know, anyone can start a business and be successful.

So I think it still resonates across many countries in the world, particularly the liberal, democratic world, that this idea even here, where I’m talking from here in Australia, it certainly, certainly is the case. And you see, you know, if you look at kids in school, a lot of them, you know, are looking at business and can be rich too.

And, you know, teenagers investing in crypto because they think it’s going to be the road to riches. So I think yeah, it’s different and it manifests differently in different countries. But I think there is a kind of global aspect of this. I mean, even go back to the days of microfinance and and all these kind of things. It’s all you know, people through their own, pulling themselves up by their own bootstraps and all of these kinds of things.

And that’s I mean, not that I’m saying initiative is a bad thing. It’s a great thing, but it’s not a reason that one person should have billions and billions of dollars and another person can’t feed their family.

MP: Yeah. No. Nicely put. On another occasion we should have a discussion about the role of business schools in spreading this particular account.

CR: Indeed we should.

MP: of how, how society should be organized. I guess let’s just move on to the final one. So this is I think it’s probably my favorite one, the myth of the vigilante billionaire. Could you talk a little bit about that Carl?

CR: Certainly. So of course we have the vigilante as a classic figure from Western culture, whether it be Batman or The Lone Ranger or even going back to Robin Hood, even the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, who are vigilantes and the vigilante, and is the person who comes into a social situation where there are big problems and the bureaucracy has, the police and the law and the courts, has not been able to to solve this.

And this person then comes in single handedly and is able to fix all the problems, mainly because they kind of operate above the law. They disregard law. They don’t, they’re not limited by it, by these things. And they can they can solve all the problems. You know, Clint Eastwood is as Dirty Harry. He was obviously a police officer, but, detective, but still, you know, he ignores the law, and it’s only him who can solve.

And, you know, if you go back in time, you will remember Charles Bronson doing the same kinds of thing. So it’s a very strong myth. Going back, you know, many hundreds of years about the vigilante and billionaires pick up on this. I mean, let’s think of Elon Musk before his current gig. Remember when he took over, Twitter when it was still called Twitter?

He didn’t say that he was making a good business investment, so he could maintain his position as the richest man in the world. He did this because he wanted to save democracy. He described himself as a free speech absolutist, you know, and the idea is that that he could solve that. And similarly, if you see what he’s doing now as the head of DOGE it’s about him and him alone solving these problems that the bureaucrats can’t do because he’s such a great hero, and he’s not just doing it at home.

He’s interfering in politics in the UK, he’s been for example. And more recently in Germany, we’ve got an election coming up here in Australia soon. I’m eager to see if he, if he gets involved in that too. And so this idea of, Jill Lepore the political historian calls it muskism, and it’s this idea of, you know, the the billionaires are some kind of great lords and the rest of us are peasants and that he, you know, Musk presents himself as a hero for humanity.

Donald Trump does the same thing, if you remember, when not this term, in the previous term, he kept using this term. I and I alone can fix it. It’s really drawing on this kind of cultural tradition of the vigilante, where the billionaire is a is, kind of a superhero, and their wealth is just proof of how great they are.

Again, justifying, billionaires. And what we end up getting is just more inequality rather than any real solution. So again, this myth of kind of glorifying billionaires, which is just playing out intensely, you know, at the moment.

MP: And it then also, draws on a series of ways of thinking about that awful term bureaucracy, doesn’t it? And the kind of the idea of the deep state, you know, or the blob or whatever the term might be as some sort of obstacle to change something along those lines. And of course, bureaucracy actually is a way in which very often liberal democratic societies ensure that all citizens have similar kinds of treatment, that we are not subject to the arbitrary whims of kings and presidents and vigilantes. But beating up on bureaucracy has always been politically quite, quite, quite a good thing for vigilantes to do.

CR: Yeah. No, I mean, it really has, I mean, and and not just bureaucracy in terms of rules, but even the division of powers in government, which are specifically a democratic system set up to limit the power of any particular individual. So we don’t go back the times of being ruled by kings and queens. That’s also, being put under question.

So the whole democratic system becomes fragile in the face of, of power that’s accrued by wealth. I mean, people, these days, the word oligarchs gets thrown around. But it’s particularly this is plutocratic oligarchs. The reason for this power is largely a function of of individual wealth. And so it really is, a new feudalism that we’re heading down, unless we can find a way to subvert it, unless we can find the political will to do something about it.

MP: Indeed. And in the last 24 hours, I think Trump announced that he was a king because he had overturned a decision by the city government of New York. But the very announcement of the idea that he’s a king is a curious one, isn’t it? In the sense that it that does rather run counter to many of the founding myths of the US, which, after all, are about the idea that this is a space of freedom, one in which, one which was established by the overthrowing of the previous order.

CR: Well, I mean, you know, the whole idea of the United States is in jeopardy because of this behavior. Look at the debates around immigration and deportation. Of course, until the early 20th century, the US had no, limits on immigration. You just kind of turned up on the boat and that was it. And, of course, you know, look at the poem on the Statue of Liberty.

It’s about, you know, welcoming everybody, no matter how poor or destitute you are. And you’ll be given a chance coming back to the American dream. But now we get, you know, I think it was Musk who was saying we should focus on immigration, on white South Africans because they’ve got lots of money. So as wealth now becomes the criteria, for being able to immigrate to the United States rather than democratic belief in opportunity for everybody.

So some of the, the founding myths of the United States are really being being usurped at the moment, potentially is American culture or this dimension of American culture strong enough to withstand this, at least for the next four years or even beyond? It’s not possible to say definitely that it is. We will. We’ll have to wait and see.

I mean, we’ll have to wait and see what what happens with this. Having said that, there’s also plenty of opposition. I think sometimes when you’re outside of the U.S. and I was there recently, we see the news of all these kind of ridiculous what’s appears to be ridiculous things that are going on. But in the United States itself, there’s there’s much more debate, there’s much more contestation.

And this is certainly not a cultural monolith over there as well. And so I think that spirit of freedom that informs democracy and not the freedom that Elon Musk talks about, which is it’s a freedom to blab on about any nonsense you want to, but actually the exercise of liberty and the belief of in liberty, is it strong enough to withstand this?

And that’s what’s playing out at the moment. But it’s certainly not just one sided. There’s plenty of discontent and debate and discussion across the United States.

MP: Those are great questions, Carl, and a good place for us to end our podcast. I guess just one of the other things I wanted to say is how pleased I was that an academic and the dean of a business school like you was engaging in these kind of debates and writing books that are clearly aimed at more than just an academic audience.

And that’s, that’s a fantastic thing to achieve, both in your previous book and in this one. Congratulations for that, and well done for writing such a great piece and such a timely one now as well.

CR: Yeah, I think this is an important thing to consider for academics more, more generally, who’ve been kind of pushed into this publish or perish of writing in fairly arcane journals, which is kind of okay. But if that’s all you do, you know, it seems to be somewhat inward looking. And, you know, we spend a lot of time thinking and researching about, what I would say important topics.

And it’s our responsibility, if we can, to, to engage more publicly in that. And that’s kind of what I’ve been trying to do in more recent years.

MP: Couldn’t agree more. Carl Rhodes, author of ‘Stinking Rich: The Four Myths of the Good Billionaire’, published by Bristol University Press. Thanks ever so much for spending time with us Carl. That was a fascinating conversation.

CR: My pleasure, Martin, thank you.