In 2024 the news was full of stories of the GMB Union’s fight for formal recognition at Amazon’s BHX4 Coventry warehouse. Yet, despite skyrocketing membership, the union narrowly lost a ballot that would have forced Amazon to grant them this recognition.

In this episode of the Transforming Business podcast, Martin Parker speaks with Tom Vickers, author of Organizing Amazon, about the union’s successes but also their unfortunate setbacks.

They discuss Amazon’s formal, and informal, stances on trade unions, the innovative approach GMB took to develop leadership for the movement from the ground up, and how the lessons learned from this campaign are not only helpful for other Amazon warehouses but for workers far beyond the Amazon ecosystem.

Available to listen here, or on your favourite podcast platform:

Tom Vickers is Associate Professor of Sociology and Director of the GMB-NTU Work Futures Research Observatory at Nottingham Trent University.

Scroll down for shownotes and transcript.

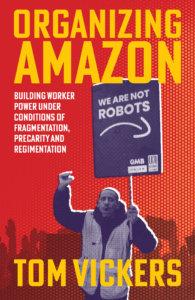

Organizing Amazon by Tom Vickers is available for £14.99 on the Bristol University Press website.

Organizing Amazon by Tom Vickers is available for £14.99 on the Bristol University Press website.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Bryan Angelo on Unsplash

SHOWNOTES

Timestamps:

00:38 – How did you start writing about Amazon?

03:37 – What is Amazon’s background with trade unions?

08:52 – Why are Amazon management so hostile to trade union organisation?

11:31 – What is the story with trade unions and Amazon’s Coventry BHX4 warehouse?

18:11 – How did the GMB work with the workforce?

23:41 – What is the present situation at the BHX4 warehouse?

27:25 – What are the general lessons we can learn from the BHX4 story?

30:25 – Do you think we’ll see more pushback with the increase of AI driven workplaces?

Transcript:

(Please note this transcript is autogenerated and may have minor inaccuracies.)

Martin Parker: Hello, everybody. Welcome to the Transforming Business podcast, and it’s my huge pleasure today to be talking to Tom Vickers about his book, ‘Organizing Amazon: Building Worker Power Under Conditions of Fragmentation, Precarity and Regimentation’. It’s a splendid book. Tom is associate professor of sociology at Nottingham Trent University and director of the GMB-NTU Work Futures Observatory. And my name is Martin Parker,

I’m a professor at the University of Bristol School of Business. So Tom, thanks ever so much for joining me today to talk about your book. Obviously highly topical in terms of the visibility and reach that a company like Amazon has. Could you tell me a little bit to start off with about how you came to be writing about Amazon?

And then we’ll get into some of the details of the book?

Tom Vickers: Sure. So this developed out of quite a long running partnership that I have round research with the GMB union, and we’ve been doing a project with them for the last couple of years about the impact of digital technologies and the way that employees are using digital technologies on workers wellbeing. And then there was a funding opportunity that came up internally within my university, and so I applied for funding from that to be able to undertake a part time secondment to the GMB union, because my experience of working with the GMB and other trade unions is that when you manage to have a conversation with an officer, you have fantastic conversations and there’s often so much, kind of, enthusiasm about cooperating with research.

But trade union officers are invariably so busy and have so many different demands on their time, and often a lot of those demands being very immediate issues that this person needs representation. These workers are under threat of redundancy. So it can be very difficult to actually schedule those conversations. So I applied for this, this pot of funding to have that part time secondment so that I could actually spend some time actually just being already in the room and already in the routine meetings that the trade union was having.

And because that ongoing research project, one of the sectors that we’re looking at is e-commerce warehouses like Amazon’s and the Midlands Organising Department of the GMB had a very active campaign underway at the time that I was doing this secondment at the Coventry warehouse particularly. And so the people I was working with in the union suggested, well, why don’t we place you with that organising department?

Because then you’ll be sort of directly in contact with the workers in Amazon and the very first meeting, when I sat down with the officers in the organising department and said, okay, I’m here, you know, how can I help during this secondment? And one of the things, first things they said was that we’re having all this success with this organising campaign.

We have hundreds and hundreds of Amazon workers joining strikes, joining the union. And so we’ve got lots of people coming to us and saying, “This is great. What can we learn from it? How are you managing to do this?” But the organisers said, you know, they were too busy actually doing the organising to sit back and actually write down what they were doing and how they were doing it.

So they asked if I could help with that, with documenting the campaign. And so it developed from there, basically.

MP: A fantastic opportunity to watch something in real time. Just to fill in some background here, because while listeners might not necessarily know now, Amazon is a company that’s been historically very hostile to trade union organisation. Can you sort of fill in some background there? Because obviously Amazon is a global company, as I said, you know, of huge importance, but a company that hasn’t entered into collective bargaining with trade unions in the vast majority of cases.

TV: That’s right, that’s right. Yeah. In the vast majority of cases, Amazon refuses to have, in most countries, Amazon refuses to have any contact with trade unions. I think the only country that comes to mind where they have managed, and this is with a lot of governmental support to get some kind of negotiation, is Italy. And that’s been a combination of governmental support and a lot of action by workers as well, supported by trade unions.

But yes, wherever Amazon can then it does not have direct contact with trade unions. Does not recognise trade unions. Even in the case, so in Coventry, they got to a point where they had a large enough membership, a big enough percentage of the workers in the union that they were granted a ballot by the CAC that oversees trade union recognition.

And but even in that situation where there was a legally mandated process that Amazon had to participate in, and they had to agree the terms for what’s called an access agreement, where a period where union officers would have access to the warehouse in order to speak to workers prior to the ballot. Even in those circumstances, Amazon refused to actually talk directly to the union.

And it was just Amazon’s lawyers were talking to the union. And through a very protracted back and forth, back and forth process. So, yes, there is a lot of hostility. Amazon’s formal position is that it is up to its employees, and it supports any employee’s right to join a trade union. That is Amazon’s formal, formal kind of public position.

What we saw in Amazon is that as workers were joining the union, and particularly as this ballot came up, which if the union had won that ballot, it would have forced Amazon to recognise the GMB at that particular warehouse. And under those circumstances, Amazon went to huge lengths to actively campaign against the trade union. They produced what can only be described as propaganda, printed propaganda, propaganda displayed on screens throughout the warehouse, directly trying to persuade workers to vote against giving the GMB recognition.

They drafted in more than 30 managers from other warehouses around the UK, who workers told me were employed just to follow workers around and talk to them 1 to 1 during the course of their work. They invited workers to what Amazon described as voluntary information sessions, as many as five or more voluntary information sessions, and this was before the access period when the trade union had access to come into the warehouse, talk to workers.

And these voluntary information sessions, which could last an hour or more, were held in a context where ordinarily workers could be disciplined for taking even a few minutes to rest that’s not an authorised part of a break. And they were being offered the opportunity to go to these voluntary information sessions during their working hours and sit down for an hour.

So, you know, there was, yes, that was obviously something that a lot of workers were going to take part in, if only to have a brief rest from really exhausting work. And in those meetings, there was constant kind of arguments being put by management. There were also reports from workers of HR phoning workers individually in the lead up to the ballot and then trying to persuade them against voting for recognition.

There were some really extreme cases of leaders amongst the workers being targeted. There was, that included one worker who had previously been moved to a different role after she collapsed at work and was taken to hospital in an ambulance due to a heart condition and the working conditions kind of impacting on her health. And so after, with support from the union, she managed to get moved to a less physically demanding role. During the ballot campaign she was then moved back on to a more physically demanding role. And this was after that, being threatened with a manager telling her that, oh well, if you believe in equality, don’t you want to be doing the same job as everyone else? So there’s this, this, this kind of implicit kind of threats being made. She was moved back onto the line, after which she again collapsed and had to be taken to hospital.

So yes, these were the kind of lengths that Amazon goes to.

MP: Yeah. I mean, the book is full of extraordinary examples of the amount of resource that Amazon management are willing to put in to prevent trade union organisation. Can we just sort of naming the elephant in the room, why do you think that Amazon management are so hostile to trade union organisation?

TV: So Amazon’s whole business model is based around a very fast and systematic speed of delivering their service, which is obviously receiving, sorting, packing, parcelling, shipping out deliveries. And that is their sort of primary competitive kind of, you know, promise against competitors is their speed of delivery. And how that translates within the warehouse is in an incredibly regimented control over workers’ movements and workers’ activity within the warehouse.

And, we did a kind of survey of published evidence on Amazon several years ago and sort of compared what seemed to be happening over time and the sort of the direction of travel. And there’s a lot of evidence that consistently points to as Amazon increasingly uses robots in its production process, that the human parts of the labor process are becoming even more regimented and even more tightly controlled.

And so that business model allows very little flexibility for individual workers needs, because where you have this very standardised process, which is all highly coordinated using a lot of machinery, the human elements of that obviously vary. We all have different needs. We all have different capacities. We all have different levels of health with different ages, but the system makes very little allowance for that.

You know, and I know of no way that it’s entered into their algorithms or the setting of rates, which people are meant to work that these kind of human characteristics are kind of built into that, I don’t I’m not aware of that happening anywhere. And so where you have trade unions that can collectively stand up for workers’ interests, that is a huge challenge to Amazon’s fundamental business model, because they want everyone controlled and mechanised and really, you know, whatever the problems in practice, whatever the problems that causes for individuals.

And, you know, you see this in the kind of the high turnover rates of Amazon staff that really they just churn through workers. And, you know, if people just get burnt out and they can’t cope, they just replace them. So trade unionism challenges that model because it stands up for workers’ needs and workers’ interests.

MP: Yeah, yeah, that’s beautifully put. So let’s move on to the specifics of the BHX warehouse, the Coventry warehouse, which you describe as a particularly central one because it’s involved in distributing things to other warehouses in other parts. So it’s a quite a large one.

TV: And strategically important. One of the UK’s only two, they’re called cross dock warehouses. That takes in bulk shipments and then splits them and sends them out to other warehouses.

MP: Yeah. Okay. Yeah. So it matters a lot to Amazon. So can you tell us a little bit of the story that’s basically from 2022 to 2024 that leads to this remarkable upsurge in some very unlikely circumstances in union organisation.

TV: Yeah, absolutely. So the story really starts in 2012. That’s when the Midlands region of the GMB started organising at Amazon warehouses, initially at another warehouse at Rugeley. And they were they learned a lot of lessons through those initial years of organising and built up a small membership. Part of Amazon’s business model is when they open up a new warehouse.

They offer workers the opportunity and sometimes give incentives for workers from existing warehouses to transfer into the new warehouse. So they’ve got a core of staff who already know what they’re doing. And so some workers transferred across when BHX4 first opened, who were already GMB members. And the union carried on doing work during the pandemic, particularly around health and safety issues.

There were concerns around working conditions not allowing workers to distance properly, but workers were classed as essential workers, so there was pressure for them to come into work. Inadequate PPE, there were these kind of issues. The union was kind of active organising with workers in Coventry. And then in 2022 there was a pay rise, which and this was after several years where there’d been no permanent pay.

There’d been a couple of sort of temporary bonuses related to the pandemic, that Amazon had given, but there’d been no, kind of, permanent pay rise since 2018. And in 2022, managers built up the idea with workers that, “Oh, you know, pay rise is coming.” And kind of built it up to be something really positive. And then when it was actually announced, it was announced to be only an extra £0.50 per hour.

And bear in mind, this is August 2022. So this was a period of very high inflation, you know, really intense period of the cost of living crisis. And so workers were seeing all their kind of, you know, their costs going up, the cost of living going up. And also this was in a context where many of the workers in the Coventry warehouse are from a migrant or refugee background and are sending money back home to support other family members.

So there’s a lot of kind of financial pressures that they’re under. And it was announced it’s only £0.50 per hour. And that sparked wildcat protests in many warehouses across the UK.

MP: When you use that term ‘wildcat’, just unpack that a bit because not everybody might be familiar.

TV: Sure. So in kind of trade union parlance, wildcat strike is, or a wildcat protest, is something that hasn’t been formally initiated through a trade union process. It is just workers just spontaneously saying, we’re not having this and then walking out. So workers staged protests in many, many warehouses, say, around the country, and shared news about what they were doing over social media.

So there are a lot of kind of workers networks that sort of spread these initial protests. And at Coventry, the protest started as a sit down protest in the cafeteria during lunch, because the warehouse is quite a divided working environment. So that was a good opportunity that the workers kind of saw you know, at that point, a lot of us, are already in the same place.

So we’re just going to sit down and refuse to return to work. A manager came down and asked workers to send a delegation upstairs to negotiate with management. But the workers said, “No, we’re… anything that you want to say to us. You can say in front of all of us”, you know, and they saw that, you know, this wasn’t going to be helpful to them to allow a small group of them to be split off and taken separately with management.

And that kept up the momentum. Management then threatened to start signing workers off so they’d lose pay. And as I say all those financial pressures, even a temporary disruption to pay, is a really serious issue for most workers in Amazon. And so then the workers decided, well, we’ve got to carry this on, but we can’t afford to lose pay.

So they arranged to meet again the next day but meet outside the warehouse. So they were kind of outside that direct control. They were then told by Amazon security that they couldn’t be protesting in the car park. So then they took the protest into the city center. And at this point, one of the workers who was already in the union, already in the GMB union, got on the phone to the organisers and said, you know, this is happening.

If you want to get into Amazon, now’s the time, come down. And it’s very important to how this developed that the union was very quick to mobilise its officers, mobilise its organisers and get them to go down and speak to the workers. And the organisers took a very sophisticated approach in engaging with the workers. So they didn’t just kind of charge in.

They took time to try and understand the dynamics amongst the workers. Right. Who are people kind of going to? Who are the kind of key people here that other people seem to be working to the leadership, looking to for leadership? And then kind of started the conversations with them and started signing workers up. They signed up people to a WhatsApp group.

As I understand it, at that time, WhatsApp had a limit. You could only have up to 500 people in a WhatsApp group. So they filled up that capacity and then set up another WhatsApp group. And it develops, yeah, it developed from there.

MP: It’s an extraordinary story, and particularly in a context where the workers are very well both divided in terms of time and space. I mean, you tell this, you know, you give this account of the warehouse in terms of just how little social contact your average worker has arriving at different times and working in very different parts of the warehouse.

And to add to that, of course, that many of these workers were migrants who were, you know, speaking different languages and perhaps had different cultural understandings of what the work employment bargain might be, and so on. So to actually get the workers organising collectively was quite an effort. So can you talk a little bit about how the GMB organisers worked with e-actors in the workforce?

TV: Yeah, yeah. And so I think this is, and I think this is really important. It’s one of the, the sort of the critical factors that enabled this campaign to be so successful was that the organisers, the paid organisers from the GMB put such a great emphasis on really listening to the workers and really sort of taking their lead from the workers and recognising who those natural leaders were amongst the workers and then working to build relationships with them and, you know, and integrate them into a more formal structure through the union.

And really sort of taking that view of trade unionism as trade unions being a vehicle to strengthen workers organisation rather than being sort of a separate organisation that does something for workers. And so they had conversations with workers about what did workers want. And workers at that point were saying, well, we want to protest. You know, we want to express, you know, we want to express our views about how we’re being treated by Amazon, but we don’t want to lose our job and we can’t afford to lose pay.

And so the trade union organisers said, well, the only way we know how to do that is through a formal strike process where, you know, we get people into the union and then we have a ballot and then people can go on strike, and then we can also support that with strike pay. There’s a kind of a hardship fund to compensate workers for the money they’re losing for those days of strike.

So, so even from quite a small initial membership, when this whole process started, there were only about 60 workers in the GMB at Coventry. And from that they started the initial ballots for strike action. They actually lost one of those initial ballots. They didn’t have quite enough people to sort of meet the legally mandated thresholds for strike action.

But the workers who were kind of leading this said, no, we really need, you know, we’ve learned lessons from it. We think we can get there. We can get there to the threshold. Next time. Let’s try again. And there were a lot of lessons learned in terms of how to reach the workers. So not just speaking to people, you know, as they were going into work, not just workers speaking to their colleagues, but also the union starting to produce initially written, translated materials.

Then they realised from feedback with workers. Actually, that’s not an effective way to reach people. And some of the languages that are spoken within the warehouse are predominantly oral languages. So they switched to things like recorded voice notes and YouTube videos and developed this whole very sophisticated setup where there would be a leaflet with a QR code, the worker gets the leaflet, scans the QR code and then that takes them to a web page, which has options for a number of different languages.

And then they click on their language and then they get a YouTube video, which is explaining to them what’s going on, what the union is about, what’s you know, what is the ballots about or whatever was happening at that time. So there was a lot of that kind of that ongoing work.

The union then recognised that they needed to identify kind of a definite leadership or develop a kind of definite leadership group among the workers. So as this process, there had been some strikes. More people were signing up on the picket line, in the lead up to strikes, after strikes. So that was building the membership. And so then the union ran a survey with all the members they had by that point, asking people a series of questions to try and identify who were the kind of nominated natural leaders. So asking workers, you know, if you have a problem at work and you know, and you don’t want to go to a manager, who do you go to? You know, questions like this. That produced a list of about 60 names and some people being nominated more than once.

The union organisers then had 1 to 1 conversations with each of those to see, you know, is that person actually prepared to be a leader? Because obviously some people might be nominated, but not be kind of happy to do that. And then from that process, they got an initial leadership group and began to organise weekly daylong leadership meetings.

And these were a combination of parts of the GMB standard training course for trade union representatives, and also very strategic discussions about whatever the latest issues in the campaign were, so that all the strategic questions could be made by the workers themselves through these leadership meetings, you know, and that was a huge, huge kind of investment from the union.

And I think that’s another element. It’s the, the kind of serious, you know, material, financial, people commitment the union made, combined with that listening to the workers about what they wanted and what their priorities were.

MP: Yeah, it’s fascinating. And a very kind of grassroots version of union organisation and particularly I’m very taken with this idea of trying to identify people who are acting in a leadership way, who are influential on the workers themselves. So, as we said at the start, the recognition ballot was unsuccessful by a relatively small number of votes, I think 17 votes or something like that.

TV: Yeah, 15 votes.

MP: 15 votes okay. Yeah. So so pretty close. But that’s back in 2024. Can you bring us up to the present in terms of what’s happening at BHX4 now.

TV: Sure sure. So under current UK trade union law, once a union has applied for recognition and then lost a ballot, they can’t then apply again for three years. So we’re in this really difficult situation at the moment where in a way Amazon’s actually more protected at its Coventry warehouse than any other warehouse in the UK because in any other UK warehouse, workers could join and then submit an application for recognition. At Coventry they can’t.

So it’s also a situation where there is really excessive staffing levels at the Coventry warehouse at the moment, because earlier in the GMB’s organising campaign, before they actually had the ballot on recognition, they previously thought they were at a point where they had enough members and so they submitted the first stage of the application for recognition.

And at that point, Amazon responded by employing more than a thousand additional workers in order to dilute that trade union membership. And this was kind of, you know, reflects kind of weaknesses in the whole kind of process for statutory trade union recognition in the UK at the moment. You know, which is a big part of the debate that’s going on with the employment rights bill at the moment, trying to resolve some of those weaknesses.

So they had this really kind of bloated workforce, basically, which led to some ridiculous situations. And, you know, workers told me about people having to arrive early for work in order to get a workstation because there were too many people for the number of workstations and then groups of workers, as many as 30 workers being told, sorry, you’re going to have to go home because we’ve not got any work for you today.

So, they have more workers than they need, and they also have lots of workers who they know are in the GMB. So what workers have told me is the Amazon are now being even more punitive than they normally are. So they have lots of rules, you know, Amazon has lots of rules about, you know, if you’re not working fast enough, if you’re, you know, I’ve talked to workers who’ve been, you know, sort of disciplined for things like, you know, in the car park system, they accidentally kind of turned the wrong direction and they were disciplined for that.

Like, there’s so many things that within Amazon’s rules, they can pull people up on. And apparently now they’re just being really, really punitive and picking up on every little thing that they’re allowed to in order to get trade unionists out the door, but also reduce the workforce, because now that they’re in this window where there can’t be an application for recognition, they don’t need all these extra workers.

So, yeah, so it is, you know, from what workers have told me, it is really tough at the moment inside the Coventry warehouse. But, you know, the membership is holding up, is holding together, the leadership group that was built through this process is still very active, is still meeting regularly, you know, is still kind of leading that struggle and also is doing a lot of work to share the lessons of that struggle to workers at other warehouses, both in the UK and internationally.

MP: That’s a great segue into the, kind of, the last bit, really, which I suppose is stepping back from Amazon a bit. I mean, Amazon is a really important company, something of a bellwether company for the global economy in some ways. But obviously, one of the things that we’re seeing is an increasing move to this kind of algorithmic management, you know, digital labour of various kinds and very often labour that separates workers from each other in a whole variety of complicated ways.

Do you think there are kind of general lessons from the BHX4 story, for the kinds of workplaces, workplaces of the future, if you like, in terms of, you know, whether we know what those are?

TV: Yes. Yeah. So I think what in a way, is even more important than the general lessons that, you know, that we identify in the book from that particular campaign. Is that campaign in the book has then provided a starting point for galvanising this international conversation, where workers are sharing their experiences of what has worked for them in their local context.

And so it’s not just people learning from the Coventry experience, it’s about workers learning from each other internationally. So a couple of weeks ago, we had an international online forum where we had 158 people there, and of whom more than 80 were Amazon workers from eight countries, all kind of sharing their experiences, you know, and how they’ve responded to some of the challenges that came up at Coventry, but come up in other places.

So I think, you know, we’re entering a really, really amazing phase. And, you know, this is kind of working together with existing international networks. So UNI Global Union has an international Make Amazon Pay campaign. There’s also a grassroots Amazon Workers International network. And so all these kind of different networks are kind of coming together to share experiences and sort of strengthen the struggle everywhere.

And partly that’s made easier because Amazon employs such an international workforce in many different places. So actually, if you get, you know, a bunch of workers together from an Amazon warehouse in San Francisco and a warehouse in Coventry, there’s a lot of overlap in the nationalities and the languages. So, you know, there’s all sorts of points of connection that actually, because of Amazon’s reliance in many countries on migrant labour, actually helps to make these kind of international linkages even easier.

MP: That’s really, really interesting. And one of the features of the book that I particularly enjoyed is the various short essays by organisers and employees, and the final one of those, by Garfield Hylton who’s a GMB worker leader at BHX4 is precisely about those kind of aspects of international organisation. It’s also kind of interesting that their reliance on migrant labour, in a sense, becomes a kind of Achilles heel for organising, as well, doesn’t it. You know, the possibility of building those kinds of alliances.

Just a last thought, and I suppose this is no more than speculation. But, you know, as we enter a kind of AI driven workplaces, there’s sort of interesting question there about the extent to which people, human beings, bodies and times are increasingly controlled by management ever more effectively. Would we therefore expect, do you think, that we’re going to get a corresponding pushback from that?

You know, you talked at the start about this idea that the human being as being, you know, part of the labour process, the work system is an obdurate part of it. You know, the human body demands different things. So the more control is demanded by, you know, the algorithm, whatever. Perhaps the more pushback we might see.

Do you think that’s a reasonable suggestion?

TV: Yeah, I think we may well see that. And a question I have and one of the areas of learning that’s going on between workers in different parts of the world at the moment is about how do you build support for Amazon workers struggle beyond the warehouse? How do you build community campaigns?

How do you sort of build the kind of infrastructure which is beyond Amazon’s control, that can support the workers that are on the frontline of that struggle? And I you know, I do wonder if there’s kind of something in there that has potential about the connection between how Amazon workers are having these kind of incredibly difficult working experiences, which are increasingly robotised and increasingly kind of managed by algorithm, and wider societal unease about the sort of the displacement of the human and the displacement of human, you know, empathy and compassion and, you know, everything that’s possible when you have humans directly involved.

So, yes, I think it will, you know, sooner or later, you know, it’ll spark more resistance. I mean, there’s a big new strike wave in Amazon warehouses in Spain that’s just been announced recently, and that’s specifically targeting the sort of the peak season coming up to Christmas so it’s going to be really interesting to see how that plays out. So I think, you know, yes, it will provoke more resistance from workers.

But I also think it’s a potential point of alliance and commonality with other sections of society as well.

MP: Thanks, Tom. That was really interesting. And it’s a strangely optimistic book as well, even though, you know, this is a book about an incredibly organised environment, it’s also a book about the ways in which people can counter organise ordinary people who can push back against some of the conditions of their oppression. So I really would recommend it to anybody who wants to understand how that kind of counter organising, in this case, particularly trade union organisation, might happen.

I’ve been talking with Tom Vickers about his book, ‘Organizing Amazon: Building Worker Power Under Conditions of Fragmentation, Precarity, and Regimentation’. It’s available from Bristol University Press. And Tom, thanks ever so much for spending time with me. That was a really, really interesting conversation, and it’s a great book. Thanks for writing it.

TV: Thank you. It’s a pleasure.