For a while, it seemed people weren’t talking about the pandemic much, trying to pretend nothing happened. But it is a memory and a trauma that is easily revived, as we have seen with the publication of the Common’s Privileges Committee Report and the release of WhatsApp messages between Matt Hancock and other government ministers.

This will no doubt continue to be relived as the Covid Inquiry proceeds. Whether we like it or not, traumatic events, though often not spoken about, still have a deep impact and can drive political change.

In her opinion piece in the Guardian on 6 February 2023, Emma Beddington asked why we haven’t been talking about the COVID-19 pandemic, given that it was so devastating for so many people. Were we trying to pretend it didn’t happen? She reminds us that Laura Spinney, in her book Pale Rider, published before COVID-19, points out that memorials to the 1918 Spanish flu, which killed 50 to 100 million people across the world, are rare, almost non-existent.

Spinney is not the only one. More recently, Guy Beiner’s volume published last year, Pandemic Re-Awakenings: The Forgotten and Unforgotten ‘Spanish’ Flu of 1918–1919, arrives at much the same conclusion. Indeed, it’s often the case that memories of horrific events seem to remain buried, at least in some quarters, for decades afterwards. The Irish famine is a good example – it was not until some 150 years later that many of the memorials were built and commemorative museums opened. Shame and humiliation perhaps has something to do with it in the case of both famine and pandemic.

Beddington argues that history may be repeating itself. COVID-19, like the Spanish flu, seems to be something we’d rather forget.

But for Spinney the absence of formal memorials doesn’t mean the flu pandemic was ‘forgotten’. Far from it. It was transformative in many ways and, she argues, had a huge impact on the formation of the modern world. She shows how it not only impacted people’s health in the aftermath and accelerated the move to healthcare for all, but shaped important political events and influenced revolutions and decolonisation struggles.

A similar thing may well be happening with COVID-19. Not the simplistic vision of a much-touted brand-new normal, perhaps, but there may be some sense in which some fairly profound change is underway. Or, indeed, some shift may already have taken place.

Many of those most deeply affected, indeed traumatised, by the appalling way their relatives, who in some cases died indescribably bleak deaths, became mere numbers in the Downing Street press conference, have turned their trauma into political action. The most obvious example is the formation of the COVID-19 Bereaved Families for Justice group, who campaigned, among other things, for a public inquiry into the handling of the pandemic, and were instrumental in the creation of the National Covid Memorial Wall.

But in different ways all of us were part of that historical moment – we could not escape it. The daily restrictions, the mounting death toll, the sense of uncertainty, the disruption to plans – events cancelled or postponed indefinitely. Underneath it all was the feeling that what seemed at first to be something that would last a matter of weeks was stretching out with no end in sight. And the recognition that we were all being asked to do things that seemed completely wrong: not to visit relatives dying in hospital, not to attend the funerals of our nearest and dearest, not to hug each other in our distress, and not to do anything other than just accept that all this was necessary.

A traumatic event is generally seen as a threat to the person themself, but often it can involve witnessing the horrific deaths of others, as I have argued elsewhere. It is an experience of utter helplessness: the person can do nothing. But, in an important sense, to be traumatic an event also has to involve a betrayal of trust. What we call trauma takes place when the very powers that we are convinced will protect us and give us security become our tormentors; when the community of which we considered ourselves members turns against us; or when our family is no longer a source of refuge but a site of danger.

There are two choices for those faced with a traumatic event: forget all about it as far as possible, perhaps by taking refuge in stories of heroism or sacrifice for the greater good, or, alternatively, refusing to forget or be ‘healed’ but instead demand social and political change.

During the pandemic, we witnessed the deaths of others at a distance, helpless, unable to attend funerals or comfort each other. At the start, our trust in the health care system was called into question when it failed to stem the deaths and failed to let us visit those in hospital. As Lucy Easthope puts it, this was ‘incredibly traumatising’: ‘It is a gross inhumanity of bad planning that people couldn’t visit the sick, view the deceased’s bodies, or attend funerals’.

More than that, the Partygate scandal demonstrated clearly that we had been betrayed by those in charge of keeping us safe: our government. Government ministers and officials had been partying as the rest of us kept to the rules. And more than that, much more, they were laughing at us, taking us for fools for obeying the regulations. The humiliation and the trauma were redoubled.

On 10 January 2022, Michael Rosen tweeted ‘May 20 2020 Number 10 party. Damn, I missed it. I was in a coma. Just my luck.’ May 20 was the day that a ‘bring-your-own-booze’ party was held in the garden of Number 10 Downing Street with over 100 staff invited to attend by the Prime Minister’s Principal Private Secretary. The replies in this thread are heart-breaking as people recount what they were doing that day.

In early December 2021, as news of the parties at the heart of government broke, the Labour Party overtook the Conservatives in the Politico national Poll of Polls. The release of a video on 7 December 2021 led to an immediate shift. By early January 2022, the Poll of Polls put the Tories on a low of 32 per cent and Labour on 41 per cent, a reversal of the position six months before. That change persists to this day, exacerbated for sure by other events since. But originating, and, it seems to me, sustained by, that switch.

What will happen when the coverage of the WhatsApp messages fades, or, later on, when the inquiry comes to an end? Will we attempt to forget the pandemic again?

I would argue that we will not forget. The trauma will persist, even if we don’t speak about it much. It will remain underground perhaps, but as a memory so deep seated that it cannot be dislodged and one that will influence what happens in the future.

Jenny Edkins is Honorary Professor of Politics at the University of Manchester and Emeritus Professor in the International Politics Department, Aberystwyth University.

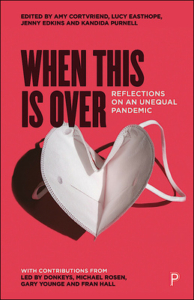

When This Is Over edited by Amy Cortvriend, Lucy Easthope, Jenny Edkins and Kandida Purnell is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £14.99.

When This Is Over edited by Amy Cortvriend, Lucy Easthope, Jenny Edkins and Kandida Purnell is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £14.99.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Ian Davidson on Alamy