There has been an international turn to participatory democracy – enabling people to play an active role in decision making that affects them – over the past three decades.

Neighbourhood planning in England is a particularly striking example of this, with community groups given the power to write statutory planning policies for their areas. This seemingly puts it at the top end of models of community empowerment, such as Sherry Arnstein’s ‘ladder of participation’, placing considerable powers directly in the hands of communities themselves.

Neighbourhood planning – and participatory governance more widely – is often portrayed as a straightforward transfer of power from state to communities. But of course, it is not the whole community who takes up these powers. In practice, a relatively small group of residents actively do the work of producing the plan. And, in common with many other participatory and governance practices, it’s not clear how the citizens involved acquire the legitimacy to wield this level of influence on behalf of their communities. While this article focuses on neighbourhood planning, the issues it discusses can be translated to a wide range of formal and informal public participation activities, where citizens or civil society groups make claims on behalf of wider communities and/or places.

One of the defining characteristics of new, localist forms of governance is their reliance on a variety of different forms of representative legitimacy, as they don’t have the authority of electoral democracy. In the case of neighbourhood planning, although most plans are initiated by parish or town councils, giving them some ‘legacy’ electoral authority, the groups who produce them often develop significant autonomy and separation from their ‘parent’ council.

While neighbourhood planning does have checks and balances built in at the end of the process – plans go through a technical examination by an independent expert, and must then pass a local referendum – in the absence of formal democratic representation, new forms of ‘situated legitimacy’ are needed to establish and maintain the power to act in the first place.

I suggest that this is done, in neighbourhood planning and beyond, by representing the issues, places and communities involved in three distinct ways: as synecdoches (meaning a part standing in for the whole), mediators and experts. These modes of representation each allow the groups to draw on different sources of authority and to make their places, communities and issues visible in different ways.

As synecdoches, groups speak as the neighbourhood: as a deeply embedded part of the neighbourhood, they stand in figuratively and practically for the wider community. Their legitimacy derives from being wholly immersed in the neighbourhood, saturated with experience of it, intimately connected to it socially and materially. It is based on their own lived experience from which has grown a deep and intimate knowledge and care. It is precisely by virtue of being affected, being moved by the community, place or issues at stake that gives the group the moral authority to act.

As mediators, groups speak for the neighbourhood, recognising that they cannot unproblematically stand in for the neighbourhood in general and that their claims to knowledge of the issues at stake rely on deep and wide engagement with the rest of the affected community. The group is distanced from its own social, material and affective entanglements in order to represent, at second hand, the experience of others. This is often formalised or codified in some way, abstracting the rich, textured detail of lived experience to categories or quantifications. These representations endow groups with a political authority, remaining connected to the neighbourhood from which they get this information and for which they subsequently speak.

As experts, groups speak about the neighbourhood, as something quite different to and separate from them. They adopt and adapt discourses and terminologies associated with professional and technical expertise. Their collective practices and experiences, in the very act of participation and representation, now differentiate them from the community at large. This enables them to produce and present knowledge or evidence as objective, untainted by their, or anyone else’s subjectivity: to speak about matters of fact. This provides an epistemological authority derived from access (albeit partial) to specialist knowledge and knowhow.

Each of these modes of representation allows groups to draw on different sources of authority. Each puts the group in a different relation to the issues, objects and communities that they represent, and in representing the world in different ways makes different versions of the world visible.

It is by combining these modes and their worlds that situated legitimacy is achieved, but there are clear conflicts between them. In many participatory arenas, in order to secure credibility with officials and institutions – seen as a necessary step towards influencing policy or decision making – the expert identity comes to dominate. While this does enable groups to exercise a degree of power and to achieve results, it also constrains the range of meanings, connections and values that can be articulated. The things that people care about, that motivate them to act in the first place, that connect the issues at stake to their everyday lives, are often squeezed out in order for some imperfect translation of them to be fitted into a rigid policy pigeonhole or institutional structure. This can be seen in situations as diverse as ‘the alienation of neighbourhood planning’, the institutional co-opting and reframing of environmental justice priorities and slum redevelopment.

This is not to deny the importance of technical information, or expert or bureaucratic framings. But when these come to dominate to the extent that the knowledges and values of lived experience are marginalised, then participatory processes are failing at their most central aim. Using this framework to analyse, design, practise and where necessary rebalance participatory practices offers a way to ensure that all the relevant and important ways of knowing people, place and issues are accounted for. It can help deliver on the promise of participatory democracy – that citizens should have more of a say over the matters that affect them – by enabling participatory practices to better engage with the things that matter to people in the ways that they matter.

Andy Yuille is Senior Research Associate with Eden Project Morecambe at Lancaster University.

Beyond Neighbourhood Planning by Andy Yuille is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £26.99. (£13.49 in our summer sale.)

Beyond Neighbourhood Planning by Andy Yuille is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £26.99. (£13.49 in our summer sale.)

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Bristol University Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

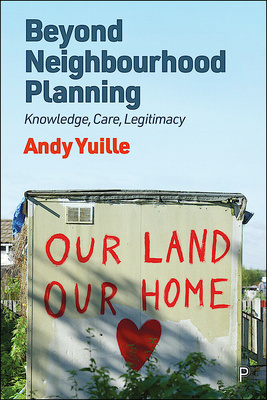

Image Gary Meulemans via Unsplash