In the UK this year alone, various scandals of ‘good’ organisations behaving ‘badly’ were revealed.

The Post Office unjustly prosecuted close to 1,000 sub-postmasters. The National Health Service’s ‘downright deception’ of giving approximately 30,000 patients contaminated blood products led to deaths, HIV and hepatitis C infections. The Charity Commission failed to properly handle serious safeguarding concerns relating to alleged sexual exploitation at a charity. And the Church of England systematically covered up allegations relating to child abuse. As these examples show, scandals of ‘bad’ behaviour are not unique to a certain sector, like health or faith, and ‘good’ organisations can be involved in various types of ‘bad’ behaviour, like abuse or negligence.

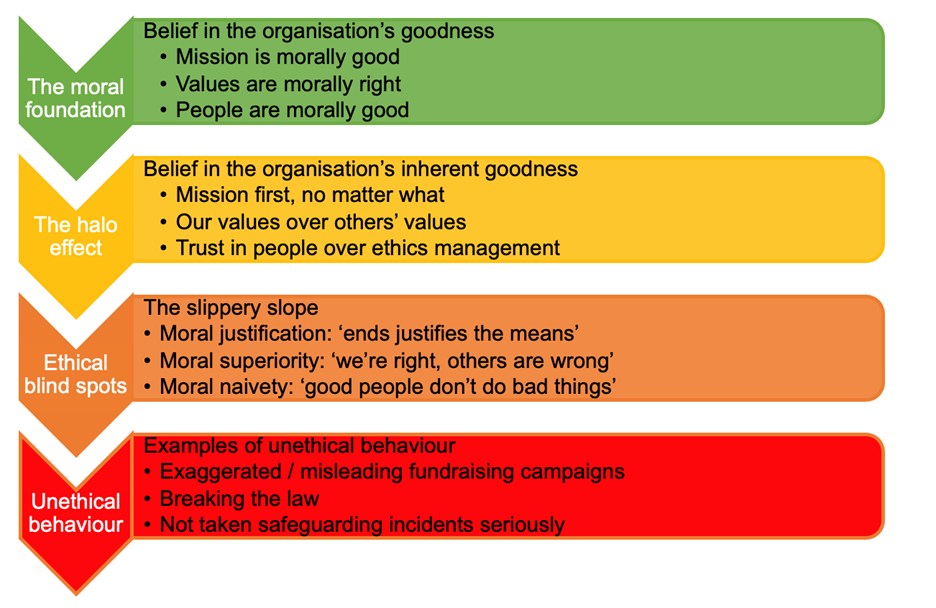

While ‘good’ organisations are not the only ones capable of bad behaviour, there is a unique factor that explains why they are particularly prone to it. Unlike big corporations such as Volkswagen, Barings Bank or KPMG – all no strangers to scandals – these organisations are distinguished by their reputation as ‘good’. This perception of goodness can lead to the organisation’s unethical behaviour. The NGO halo effect illustrates how individuals working or volunteering in ‘good’ organisations can glorify the goodness of their organisation, leading to moral blinds that enable their unethical behaviour.

The NGO halo effect

Rooted in the altruistic nature of non-governmental – or charity – organisations (NGOs), the NGO halo effect arises from their distinct purpose of serving the public good rather than pursuing profit. The term refers to the tendency of individuals within such organisations to glorify the goodness of their mission, values and people, leading to a distorted perception of what can typically be considered ethical behaviour.

A glorified mission can foster tunnel vision, where achieving organisational goals becomes the sole priority. In such cases, employees and volunteers may justify questionable actions under the guise of advancing the mission. Psychological mechanisms such as moral justification play a key role, allowing individuals to rationalise unethical actions as serving a higher purpose. For example, NGOs might downplay environmental impacts or bypass regulatory compliance to deliver aid swiftly, rationalising these as necessary sacrifices for the greater good. This ‘ends-justify-the-means’ mentality blurs ethical boundaries, making unethical actions more likely.

Similarly, glorified values can create a sense of moral superiority, where individuals prioritise their organisation’s moral framework over societal norms and legal standards. When an organisation’s values are regarded as paramount, they are often treated internally as the ultimate standard for determining what is right or wrong – potentially diverging from the ethical or legal views held by external stakeholders. This glorified belief can lead the organisation not to conform to laws or socially accepted norms of what is moral or immoral, under the pretext that they possess the authority and right to act according to their own moral principles. For example, Women on Waves’s offer of abortion services in countries where it is illegal shows how they prioritise their own values over compliance with local laws.

Finally, glorifying individuals within NGOs can lead to moral naivety, where staff and volunteers are seen as inherently good. This glorification can create a blurred line between the belief that people are inherently good and the reality that even good people can engage in unethical behaviour. This idealisation undermines the need for robust ethics management, as trust in people supersedes the need for oversight. For instance, leniency after serious misconduct can signal that ethical behaviour is assumed rather than enforced, weakening organisational integrity.

This visual explains the NGO halo effect:

Implications of the NGO halo effect

Why are the findings behind the NGO halo effect critical to transforming society? Einstein famously suggested he would spend 59 minutes defining a problem and only one minute solving it – highlighting that the rigour with which a problem is defined is the most important factor in finding an effective solution. While the NGO halo effect is not the sole explanation for unethical behaviour, it is the only one that problematises such behaviour in accordance with what makes such organisations distinct: their perception of being inherently virtuous.

Understanding the problem of unethical behaviour through the lens of the NGO halo effect has implications for how we solve it. Here are three reflection questions to help individuals in ‘good’ organisations identify their moral blind spots and reduce the risk of the halo effect:

- To what extent do you overemphasise mission achievement? While the organisation’s mission is important to fostering purpose and driving positive change, it should not be treated as an infallible guide. Instead, the mission should serve as a framework balanced with organisational ethical and legal standards. Prioritising this balance, rather than mission achievement, can reduce the possibility of the halo effect.

- To what extent do you believe your organisation always knows what is ‘right’ or ‘moral’? While the organisation’s values are important to define the moral character of the organisation, a strong belief that it inherently knows what is right can lead it to dismiss others’ norms as irrelevant or acceptable to violate. Ensuring that external ethical benchmarks are integrated into decision-making processes helps prevent organisational values from overriding broader ethical requirements, reducing the risk of the halo effect.

- To what extent do you consider your colleagues as inherently trustworthy? While it is important to foster trust within teams, assuming that colleagues will always act ethically can lead to underestimating the need for oversight and accountability. Ensuring that trust is balanced with clear ethical guidelines, such as codes of conduct, and accountability mechanisms, such as whistleblowing procedures, can reduce the possibility of the halo effect.

Isabel de Bruin Cardoso is a lecturer and researcher at the Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, and a visiting lecturer at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. She consults with a range of charity organisations on ethics management and sits on various charity boards.

Exploring the dark side of NGO moral goodness: a conceptual framework on the NGO halo and its role in unethical behaviour by Isabel de Bruin Cardoso, Muel Kaptein and Lucas Meijs is available to read open access on Bristol University Press Digital here.

Exploring the dark side of NGO moral goodness: a conceptual framework on the NGO halo and its role in unethical behaviour by Isabel de Bruin Cardoso, Muel Kaptein and Lucas Meijs is available to read open access on Bristol University Press Digital here.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Bristol University Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Ronald Plett via Unsplash