At last, Taylor Swift gave her coveted endorsement to Kamala Harris, which crowned an impressive debate night for the Vice President. When the pop star bestows her blessing, it’s a big deal. Show me another ‘childless cat lady’ who causes actual tremors around the world. Swift wields the sort of outsized influence that can turn out the youth vote, whereas Donald Trump has no such star power by his side, save an AI fake.

But who needs big celebrity endorsements when you have an invisible wind at your back? Trump enjoys a worldwide web of shadow endorsements that recruit more youth – young men, especially – than the brightest stars. It’s called the ‘manosphere’, and it’s the emotional engine powering the far right around the world. Manosphere should be a household name, but it isn’t. Coined in the 2010s, the term captures a global network of online misogyny, which surged during that period and has since metastasised.

Today, the manosphere targets young men with endless anti-feminist brands (yes, brands), from Andrew Tate’s brash ‘hustler’ to the bespoke-clad tutelage of Jordan Peterson. No mere outpost for grumpy old men, this is a space where Fight Club meets The Matrix. Or so it says, presenting a diverse menu of masculinities that feed the urge for an edge. The manosphere speaks directly to that vulnerable male self who longs to be cool, then delivers the relief he craves: “You are in-the-know and on to something, countercultural even. You are better than them.”

For all its variety, the manosphere sells one signature feeling: aggrieved manhood. The gnawing conviction that real manliness, especially the straight white Western kind, is under attack and must fight back. Aggrieved manhood is a ‘gateway drug’ to the far right, and the manosphere is its pusher. Right now, this ‘red pill’ feeling is spreading like wildfire among young men because the manosphere lights the blaze and fans the flames. Online 24/7 and still gaining steam, this global network gives Trump and other so-called strongmen (and women like Italy’s Giorgia Meloni) what no celebrity could: an enormous, contagious energy source that is both invisible and renewable.

The manosphere overlaps so much with the far right that any distinction is difficult. Consider ‘replacement theory’, a far-right notion now familiar to the mainstream, which holds that immigration threatens to ‘brown’ majority white Western countries. Less known is the crucial role of misogyny in this kind of white supremacist nationalism. Basically, replacement theory holds white women liable for the population shift. Distracted by careers thanks to feminism, ‘childless cat ladies’ like Taylor Swift fail their reproductive duties (in case you’ve wondered why she’s a favourite far-right target). Recall how manosphere friend and funder Elon Musk recently countered Swift’s endorsement by declaring: “I will give you a child and guard your cats with my life.” Now you know what he’s on about.

Or consider groups like the Proud Boys, who – in name and membership – feature the starring role of manly entitlement in their quest to save Western civilisation. Yet they are routinely called ‘far-right’ agitators with little to no mention of gender. Why do we keep missing how misogyny completes the puzzle? Give the manosphere its due, and a bigger picture comes into view.

Don’t underestimate the manosphere as some creepy corner of the internet for disaffected dudes. Long ago, it blew out any virtual walls said to contain it. In case you haven’t noticed, manly grievance vibes are everywhere. The feeling that real men have been victimised by decades of gender, sexual and racial justice efforts – that straight white guys now have it the worst – saturates public and private life. Aggrieved manhood flows easily from screen to living room, from school to pub and voting booth. Borders are no match for its simple gender binary (‘manly rights, wronged’), which is readily stackable with the local, personal resentments of men old and young.

It is no exaggeration to say that aggrieved manhood has gone viral, super-spread by the manosphere. This is not another tired pandemic metaphor. We are talking about something that exceeds individual ideological radicalisation, a phenomenon more insidious and infectious. The manosphere operates by physical radicalisation, priming bodies all over the world to crave the rush of escalating outrage and explosive retaliation that aggrieved manhood delivers. Through aggressive, often violent play, the senses calibrate to radical content. It is through these doors of feeling that the manosphere works best, getting the body on board before awareness catches up.

Now here comes the worst part. Day in and day out, the manosphere struts aggrieved manhood before our sons, vying for their attentions and passions early on. As a professor who teaches college-aged men about gender and communication, my heart breaks at their firsthand tales. My job is to listen and help them wade through it – at the level of emotion, not just ideas or information. When we talk about ‘toxic’ masculinity, they cringe, worn down by the manosphere’s backlash to that concept. They want to know that we know about aggrieved manhood, and that we have their backs as young men struggling with it. Do we?

For all their seismic energy, even Swifties can’t compete with the momentum made by a power plant like the manosphere. The time has come to learn its name and address it head-on. We can start by having gentle, curious conversations with the young men we love.

Karen Lee Ashcraft is Professor of Communication at the University of Colorado Boulder. She grew up in the lap of evangelical populism, and her research examines how gender interacts with race, class, sexuality and more to shape organisational and cultural politics.

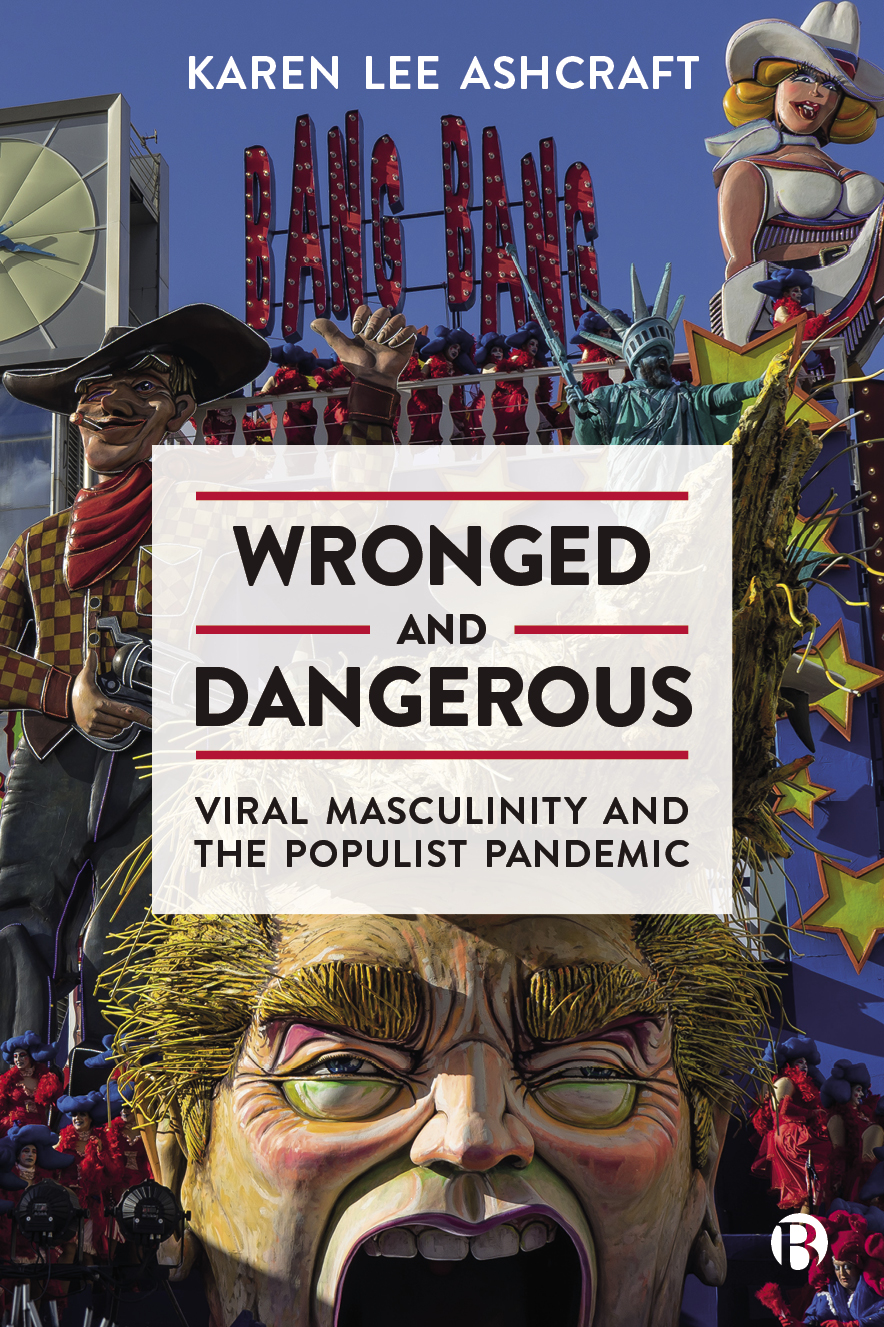

Wronged and Dangerous by Karen Lee Ashcraft is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £19.99.

Wronged and Dangerous by Karen Lee Ashcraft is available on the Bristol University Press website. Order here for £19.99.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image: Khudoliy via Shutterstock