Humanity has explored less of the world’s oceans than it has of outer space. We are living in a time in which billionaires compete to see who can get their own spaceship into orbit first. An ecological crisis, that large swathes of humanity will likely struggle to survive, is ever-growing.

Last week a suspected 100 refugee children died off the coast of Greece when the boat they were on sank. The Greek authorities did little to save them. This week a group of millionaires and billionaires boarded a barely functional submersible craft not designed to go to the lowest depths of the ocean and proceeded to attempt to visit the wreckage of the Titanic, not for research purposes, but for pleasure.

The culmination of this was the launch of an international rescue effort. Social media was awash with people mocking the passengers’ precarious situation and the stepson of one of them was forced to delete their social media account after posting a picture at a concert. Meanwhile, the 24-hour news-cycle scraped the bottom of the moral barrel and began a countdown clock.

It is within this context that this blog seems worth writing. All five passengers have now unfortunately been confirmed deceased from this entirely avoidable disaster. We would normally avoid commenting on such incidents from an ethical basis. But an ethical stance appears to be rather redundant at this stage and it feels like the right time to ask “How did we get here?”

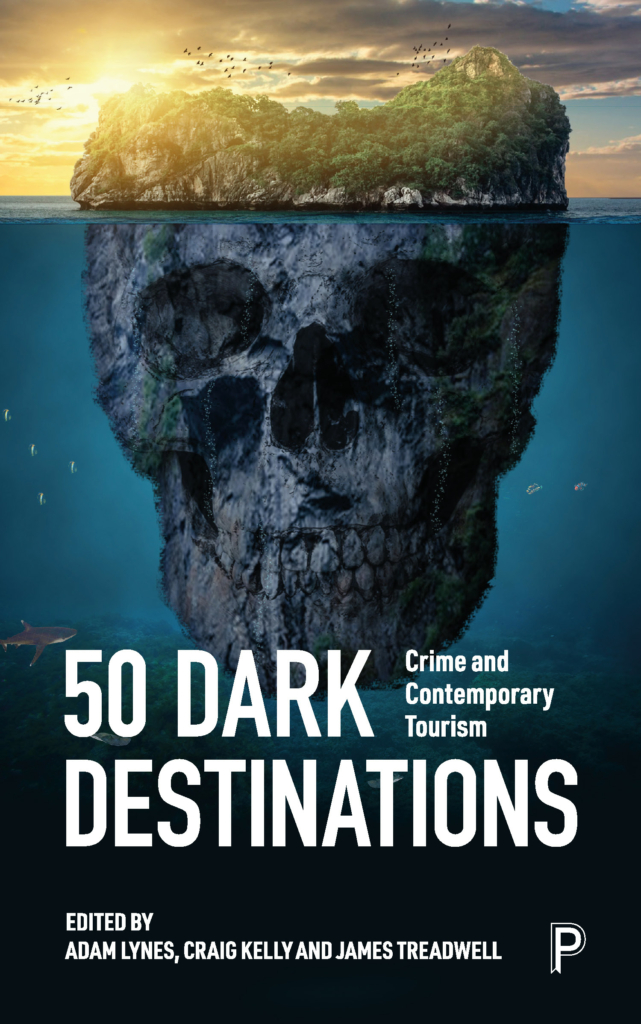

The trip to the Titanic is, without doubt, a form of dark tourism. As discussed in the recently released 50 Dark Destinations, death-related tourism and leisure can be seen throughout human history. The visit to a site of death (often referred to as ‘thanatourism’) is far from unique and, arguably, much more embedded in our shared social norms than we would care to admit. What makes the OceanGate tragedy unique is the luxury tourism aspect.

In recent years, the way in which individuals engage with sites of tragedy has changed, reflective of wider changes in consumer tourism patterns. This is perhaps best demonstrated by the mass of tourists each day who are furiously snapping away on their iPhones at Ground Zero, in the middle of Choeung Ek killing fields or on the tracks leading into Auschwitz. Such behaviour is symptomatic of the nature of contemporary consumer culture. Life is ever more competitive, whilst consumer culture has ironically unified notions of individuality, extracting unique aspects of subculture and commodifying them.

As Oliver Smith argued in 2019, “the drift towards luxury in the tourist industry compounds, exacerbates and perpetuates environmental and cultural harms on a local and global scale”. Within this discussion, he highlights those luxurious forms of tourism, such as private villas and Michelin starred restaurants, are no longer the preserve of the super-rich. Increasingly, a wider range of consumers can access these overt signs of wealth and status. Such changes create clear obstacles for the super-rich to display their ‘unique’ identity, forcing the luxury consumer experience to adapt. Within this context, Smith offers the examples of canned hunting, private flights and skiing. More extreme examples, a mere few years later, are trips to space or to the wreck of the Titanic.

It should be no surprise that, as extreme forms of luxury tourism expand, conflation and cross-over with thanatourism increases. Alongside this, the extremity of the experience is seemingly growing ever more risky. As Featherstone observes in his analysis of Marquis de Sade and the sexual libertine, criminal luxury is comparable to contemporary culture. Extreme luxury and criminal transgression are viewed as normal and necessary to the global system, though harmful to those around them. Clear comparisons can be drawn between the extremities of luxury and transgression within Featherstone’s analysis and the contemporary super-rich luxury tourists. It is at this stage that we should probably re-highlight the ecological crisis unfolding around the world and the dozens of children who have lost their lives trying to seek refuge in Europe, in stark contrast to those who can have everything but continually seek riskier, more individualised and unique experiences. What they do may not be illegal, but it is definitely harmful.

Behind all this are the conditions of this luxury expedition. A submarine (operated by a cheap controller) was highlighted as dangerous on numerous occasions. Each tourist who embarked on the trip was charged $250,000. This is a rather exceptional aspect: it is usually the poor who are subjected to harms arising from those who ignore basic safety in the pursuit of profit. Instead, we are arguably witnessing an imbalance of basic safety with the desire to escape the banalities of luxury life. Underpinned by hubris, the danger has been commodified in pursuit of pleasure. However, unlike when the poor are in danger in the ocean, a large-scale rescue mission was undertaken.

On a recent social media post, one of the authors of this blog half-joked that Netflix would already be writing a script about what we were witnessing unfold. We say half joked as, running concurrent to the changes in luxury tourism, is the increased popularity of true crime driven by streaming platforms. Within this context, we see the emergence of a yearning for individuality alongside an increasingly detached notion of victimhood, where tragedy becomes the fixation of an evening’s entertainment. The nature of consumerism has also changed. Platforms such as YouTube and TikTok have broken down the barriers between entertainers and the public, democratising entertainment. The result of these toxic changes in consumerism are perhaps best exemplified by the infamous video of Logan Paul, the Youtuber who faced backlash in late 2017 after posting the video of a deceased man in Aokigahara, Japan (more commonly known as the ‘Suicide Forest’). Clear comparisons can be made between wider society’s fascination with violence and the deaths we watched unfold alongside a countdown clock.

We live in a world of contrast. While many struggle to pay their bills, others jet off to the Maldives. Those fleeing famine and war in the Global South drown in the Mediterranean as the authorities watch on. Whereas, when the super-rich sign disclaimers and climb aboard a barely functioning sub, international rescue missions are launched. It is these contradictions that prop up the global tourism industry and, indeed, the wider global system.

Adam Lynes is Senior Lecturer in Criminology at Birmingham City University.

Craig Kelly is Lecturer in Criminology at Birmingham City University.

James Treadwell is Professor in Criminology at Staffordshire University.

Max Hart, Lecturer in Criminology at Birmingham City University

50 Dark Destinations by Adam Lynes, Craig Kelly and James Treadwell is available on the Policy Press website. Order here for £12.99. (Currently £6.49 in our summer sale.)

50 Dark Destinations by Adam Lynes, Craig Kelly and James Treadwell is available on the Policy Press website. Order here for £12.99. (Currently £6.49 in our summer sale.)

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Bristol University Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Rokas Tenys via Alamy