Annual levels of global oil consumption continue to grow and are projected to reach more than 100 million barrels per day. Imagining or enacting the ‘end of oil’ may appear, at best, a theoretical enterprise. Yet the need is clear. The realities of climate breakdown are as visible as ever – countless records have already been broken in 2023 – reaffirming the imperative to radically and rapidly reduce how much oil the world extracts and burns.

While the power and responsibility to take such actions are unfairly distributed and grossly misgoverned – five industrialised countries with the greatest economic means to phase out production are responsible for a majority of currently planned oil and gas expansion – there are some signs of change across the energy sector. Chile has decommissioned eight coal-fired power plants and 12 more are scheduled to stop by 2025 or earlier, and California has issued a record-low number of new oil permits (although the number is not yet zero and reworking permits continue). The phase-in of renewable power sources continues to support energy transitions away from a purely hydrocarbon-based energy mix. Transitions, however, are not as linear as they appear. For climate change mitigation to be effective and to meet diverse demands for environmental justice, energy transitions need also to address extractive histories and the toxic legacies of an oil industry now over 100 years old. The decommissioning of disused fossil fuel infrastructures will be central to these efforts.

It is not known how many oil and gas wells have been drilled around the world. While extraction continues from millions of active wells, many more have reached the end of their productive life and are currently sitting idle, unused or abandoned by their former operators. One calculation estimates more than 29 million abandoned oil and gas wells exist globally, emitting 2.5 million tons of methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

The US alone accounts for more than a third of oil and gas expansion planned globally by 2050. Already in the US, at least 14 million people live within a mile of an abandoned oil or gas well (including 1.3 million adults with asthma), creating pollution that is concentrated among low-income areas and communities of colour. Approximately three of five US oil and gas wells ever drilled are currently inactive and barely half of these have been plugged. The scale is staggering. In recent months, accounts have been shared of hundreds of abandoned oil wells leaking methane, crude and other toxic substances off the coast of Texas; thousands of old wells in disuse are emitting carcinogens across Pennsylvania; and countless cases exist in California. Orphaned wells in residential areas of Los Angeles are linked to severe health issues for neighbouring residents. Further north along the coast at Summerland Beach, hundreds of continuously leaking wells, which date back to the world’s first offshore oil wells in the 1890s, are now being targeted for ‘re-abandonment’. The wildcatters who first abandoned them in the 1930s just walked away or plugged them with clothing, rags or wood.

The imperatives and objectives of transitions look very different within different political, social and economic conditions. Frequently, though, the transitions concept focuses strictly on the future and the promise of different (usually technological) ‘solutions’. Though this orientation is purpose-driven, it has shortcomings. Often obscured from view are past or ongoing struggles for environmental justice and transformative social change. Alternative approaches instead root the need for transitions within those struggles for systemic change, framing energy transitions as broader projects of social and ecological transformation (rather than merely substitution), emphasizing how much it matters who calls for, leads, works on and contributes to such processes. Transitions require both future planning and historical reckoning – identifying how past forms of industrial activity limit the potential for positive contemporary change and development.

Without responsible fossil fuel decommissioning, meaningful energy transitions will remain impossible. Prior energy systems do not neatly come to an ‘end’. The standard focus on metrics (such as renewable energy output or greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere) tends to ignore what historians of energy have repeatedly shown: that societies always tend to use more of everything. A standard policy focus also risks obscuring the ongoing forms of toxicity that affected communities endure at and around now disused fossil fuel sites. Many energy-related injustices are routinely overlooked by decision makers when those injustices fall outside the formal remit of environmental impact assessments, occur in places that are disconnected from active sites of combustion and consumption, or take place on timescales that are longer or more unpredictable than commonly recognised energy impacts. Energy transitions thus require governing authorities to enforce comprehensive decommissioning frameworks, holding extractive corporations to account.

The costs involved in decommissioning projects are significant, raising urgent questions about responsibility and whether companies who have profited from the sale of extracted resources will be held liable for clean-up and remediation costs. Unlike building and permitting, there is no regulatory playbook for fossil fuel decommissioning. Never before have industrialists or governments invested in closure on a large scale. Climate activists rightly call for an immediate end to investment in, subsidising of and construction of fossil fuel infrastructures. And long-term plans for this transition are also required. Abandoned infrastructures continue to have an afterlife of destruction that persists long after the end of their apparent economic utility. The safe and effective decommissioning of such fossil fuel infrastructures is one of many contributing actions that will enable the construction of more just and healthy energy systems.

Tristan Partridge is a Lecturer in Global Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and co-founder of the CREW Center for Restorative Environmental Work.

Javiera Barandiaran is Associate Professor in Global Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and director of UCSB’s Center for Restorative Environmental Work.

Decommissioning: another critical challenge for energy transitions by Tristan Partridge, Javiera Barandiaran, Nick Triozzi, and Vanessa Toni Valtierra. Read Open Access on Bristol University Press Digital.

Decommissioning: another critical challenge for energy transitions by Tristan Partridge, Javiera Barandiaran, Nick Triozzi, and Vanessa Toni Valtierra. Read Open Access on Bristol University Press Digital.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Bristol University Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

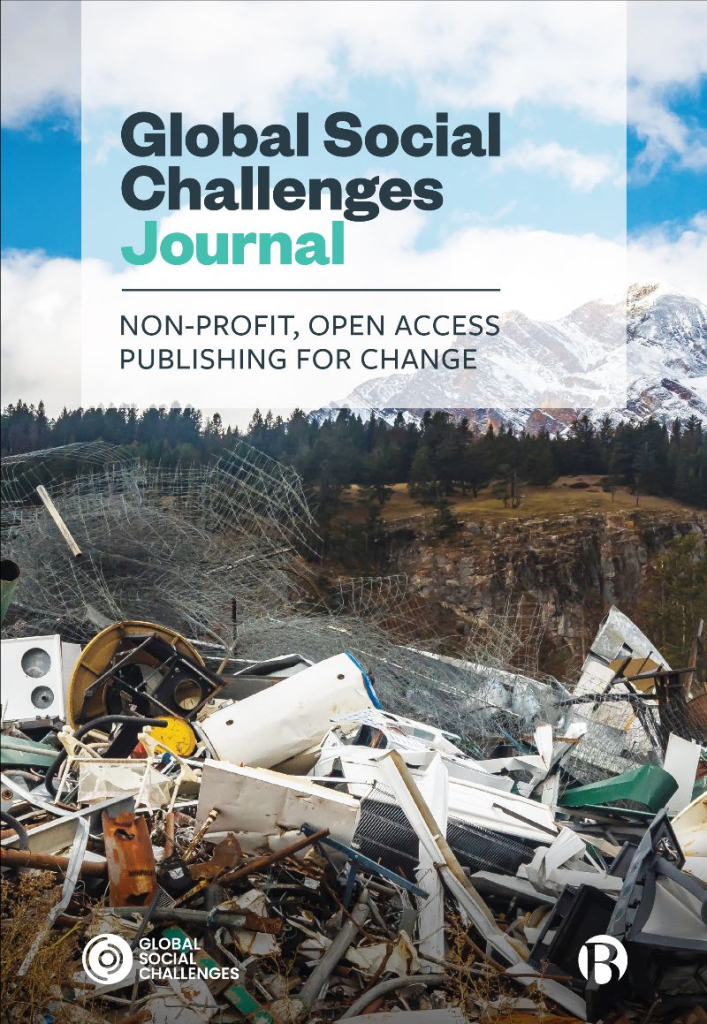

Image credit: Marcin Jozwiak on Unsplash